My article “Surveillance Society: The Mass-Observation Movement and the Meaning of Everyday Life” is in the 11 September 2006 issue of The New Yorker. Herewith a few acknowledgments and extras (as usual, what follows will make more sense if you read the article first). . . .

My foremost debt is to the book under review, Nick Hubble’s Mass-Observation and Everyday Life: Culture, History, and Theory (Palgrave Macmillan, $85) (table of contents and sample chapter here). I also owe a great deal to two biographies, both of which are great reads: Judith M. Heimann’s The Most Offending Soul Alive: Tom Harrisson and His Remarkable Life (University of Hawaii Press, $26.95) and Kevin Jackson’s Humphrey Jennings (Picador, £19.80).

Mass-Observation itself is still around, or rather, is around again. As Dorothy Sheridan, Brian Street, and David Bloome explain in Writing Ourselves: Mass-Observation and Literacy Practices, it was revived by the University of Sussex in time to recruit day-surveys for the 1981 wedding of Charles and Diana, and the project is ongoing. You can explore the archive here; they also have a wonderfully comprehensive bibliography. The webpage of the reincarnated Mass-Observation specifies that they are “currently only recruiting male writers aged 16-44 living in all regions of the UK except the South East and South West,” but if you meet those criteria, you can enlist here.

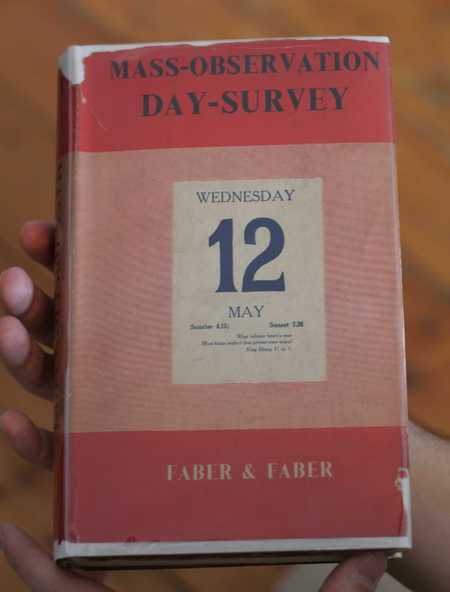

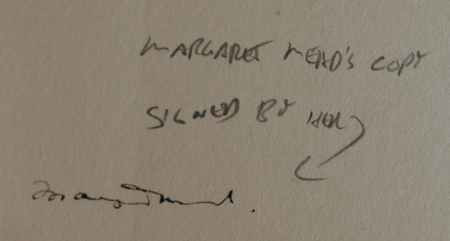

The genesis of my article is unusually ancient. When I was in college, I found a copy of May the Twelfth (photographed above) in a used-book store and couldn’t figure out what it was. Since it only cost $8.50 and happened to be signed by Margaret Mead (a fact the bookseller helpfully glossed, in case would-be purchasers couldn’t read her handwriting), I bought it.

It wasn’t until more than a decade later that I read May the Twelfth and looked into who and what Mass-Observation were, and then, when I noticed Hubble’s book was coming out, suggested the idea to my editor.

The city of Bolton, which Mass-Observation referred to in print as “Worktown,” to give it a modicum of privacy, seems to have embraced the M-O legacy. The Bolton Museums Art Gallery and Aquarium has made scores of Humphrey Spender’s documentary photographs available in an online exhibition, Humphrey Spender’s ‘Worktown.’ Here, for example, is the supposed ex-cannibal Tom Harrisson shaving himself, using a dish as a hand-mirror, in the tumbledown M-O office at 85 Davenport Street (the one that stank of fish and chips), and here are a few men drinking in a Bolton pub. It’s hard to see the quality of Spender’s photos from these online samples; for that, Deborah Frizzell’s Humphrey Spender’s Humanist Landscapes: Photo-Documents, 1932-1942 is well worth the $45 price tag.

The easiest way for an American to see Humphrey Jennings’s films is by purchasing or renting Listen to Britain and Other Films (Image Entertainment, 2002), which is in the NTSC coding compatible with U.S. televisions. Unfortunately, Spare Time, the film I discuss in my article, isn’t included and is rather hard to track down. (The Museum of Modern Art’s film library arranged a screening for me, for which I’m incredibly grateful.) A few minutes from Spare Time appear in Rebecca Baron’s How Little We Know of Our Neighbours (49 min., 2005), a meditative documentary on Mass-Observation and on the nature of surveillance in society today, so try to catch it if screens at a festival near you. Baron’s film also features interviews she conducted with Humphrey Spender not long before he died—a real treat. (If you’re British—or rather, if your VCR and television are—you could see Spare Time on the British Film Institute’s video Britain in the Thirties and Jennings’s other films on The Humphrey Jennings Collection (Film First, 2005), both encoded in PAL. (Note: I haven’t viewed these last two titles, since my television is confiningly American.) Finally, the Criterion Collection has included Listen to Britain, one of Jennings’s wartime documentaries, on its DVD of A Canterbury Tale.

You can hear a Wurlitzer band organ playing an early 1939 performance of “The Lambeth Walk” from a paper roll on Gary Watkins and Matthew Caulfield’s online catalog of Wurlitzer music rolls. You can hear the American singer Eddie Cantor’s version here. The chorus in Spare Time who sing Handel while they help their pianist take off her coat are singing “Ombra mai fù.” I can’t seem to find a free 1930s version this morning, though Enrico Caruso does sing it; here, instead, is a cello-andano arrangement from 1908, taken from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project.

This is fascinating information, and I am grateful for the range of links. As editor of a website devoted to the culture of world football (soccer), I am intrigued that the "anthropology of football pools" was indicated as one of the targets of observation. George Orwell had mentioned the football pool phenomenon briefly in "Road to Wigan Pier." I am wondering if such observations, either of the football pools or football culture in general, were undertaken by the Mass Observation surveys, and if there is a resource to which I might turn. Many thanks again for your helpful articles and research.

I appreciate this feedback and detail about the football pools. I mentioned some of George Orwell's comments about the pools in a footnote at http://www.theglobalgame.com/london02.html, and I'm always curious to learn more about this faded aspect of life in day-to-day Britain.

Hi, John Turnbull; thanks for your note and the kind words. M-O did report on football pools in a chapter of their book First Year's Work, 1937-38, ed. Charles Madge and Tom Harrisson (London: Lindsay Drummond, 1938). They reported that in the town they surveyed, a third of the population played the pools, and that for purposes of social mingling, the pools were "as essential as smoking and swearing." There's even an illustration of a pen-sized device sold at Woolworth's that generated pool numbers. The Mass-Observation writers seem to have taken a dim view of the pools, which one player described as "like a sort of growth that eats into one," and thought they preyed on workers' fantasies of escape. (The inference, I imagine, is that the desires would have been more productive if channeled into the labor movement.) The observers reported, however, that those who played the pools thought that people who opposed them did so because they wanted to keep the working class down. Politicians who attacked the pools in a moral tone were thus doomed to fail, and M-O advised them to pay closer attention.

I'm sure there's something on the culture of football more generally in the M-O archive at Sussex. There seems to be a file of press clippings and observers' description of football matches in file 82/2/E, for instance, and there's probably more in other files. I haven't yet had the good luck to visit the archive myself; you can make an appointment here.

Is it trite to point out that so many bloggers seem to have volunteered for the Mass Observation effort without knowing it? The blogs are at least a ripe source of information concerning "outdoor copulations," among — of course — many, many other things.

But in all seriousness, look at the many different accounts of important events that are captured, not by journalists who have raced to the heart of the action, but by "average" people who happen to record how their "normal" lives were affected. The London bombings leap to mind as one prime example.

Anyway, great article. I read it just the day after a box arrived from Amazon with two Benjamin titles that feel connected somehow, "Berlin Childhood…" and "Arcades Project." It really is all connected.

Not at all trite, at least in my opinion. When I first pitched the idea to the magazine, I thought the analogy to blogs was going to be my lead (or 'lede,' to spell journalistically). In the event, there were so many other things I wanted to cram in that blogs were edged out, but I still think the analogy obtains. Thanks for the kind words, and enjoy the Benjamin.

I really enjoyed the article which I just found tonight. Thanks for the kind words about my book (and yes it is a bit too academic in tone but there were unavoidable reasons for that and I hope to write more reader-friendly but no less insightful stuff on M-O in the future).

Noting the post likening M-O to Walter Benjamin, I would just add that this correspondence excited me too and my whole engagement with the ideas in the book started with an MA thesis entitled 'Walter Benjamin and the Theory of Mass-Observation'.

Very glad to hear you liked the article; thanks, in turn, for your kind words; and thanks, again, for having written such a thoughtful and well-researched book. I look forward to seeing what you write next on M-O. (And I'm beginning to think I'd better crack open some Benjamin, whom I haven't read since early grad school days.)