An article of mine about a nineteenth-century con man and kidnapper is in the latest issue of American Literary History, a scholarly journal, and this morning my offprints arrived. I don’t think the world outside academia knows what offprints are any more, if they ever did. I say this with some confidence because when I gave one to a very worldly and well-read acquaintance, he asked, a few weeks after reading it, what it was. Had I had my essay privately printed? he asked. And that was more than a decade ago. I would like to assure everyone that not even I am so nineteenth-century as to have my essays privately printed.

Offprints are unbound printed pages of an article, which a scholarly journal provides to the article’s author so that he may share them with colleagues. The protocol is — or rather, was — that when a researcher wanted to read an article that happened to appear in a journal he didn’t subscribe to, he would send a postcard to the author, care of his institutional address, asking for an offprint. And the author, as a matter of scholarly courtesy, would mail it to him free. My father is a scientist, and when I was little and collected stamps, most of them came from the postcards sent to him and the other scientists at his institution, requesting offprints. In those days, the 1970s and 1980s, the requests by and large came from developing countries, where the research institutions had less money for their libraries. The postcards came from all over the world, in other words, from countries I’d never heard of and imagined I would never see, and it gave me a thrill to see them, emblems of the glamour and global reach of the life of the mind.

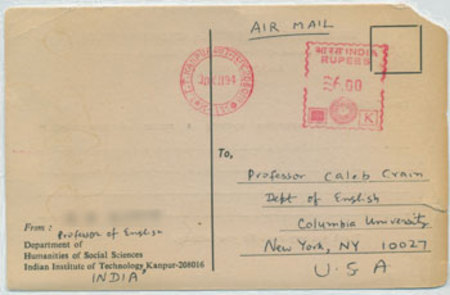

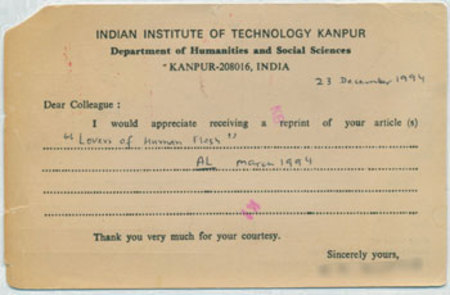

It tickled me, therefore, when, upon the publication of my first scholarly article in 1994, I received a request for an offprint.

I mailed the offprint to India very gladly. It was, unfortunately, the last such request I ever got, as well as the first, even though I’ve published several more scholarly articles since then. I don’t know whether offprints are still traded for postcards in the sciences. But in the humanities, at least to my knowledge, the use of them has degenerated to attaching them to job applications or to tenure files. The only people who see them today, in other words, are people operating in a supervisory or fiduciary capacity; the sharing of research is done through online databases like ProQuest, Project Muse, and JSTOR. Offprints are now just prettier versions of a photocopy; including one in your file is roughly equivalent to printing your resume on cream-colored paper instead of on flat white. The romance, in other words, has seeped out of it.

I have two dozen of them on my hands, however. So here’s the proposal: send me a postcard, a real one, on paper, and I’ll mail you an offprint. There is a slight advantage to the paper copy, actually; I couldn’t get online rights for one of the images, so that picture doesn’t appear in JSTOR, only in the printed version. But by and large the only cash value of what I’m offering will be best appreciated by collector geeks, the sort of people who worry whether they’ve been sold an original of the first issue of n+1 or a reprinting. Or for people who, like me, economize on printer cartridges. While supplies last, then, send a postcard to [sorry—address deleted for now, November 2016], and I’ll send you an offprint. Don’t forget to include your own snail-mail address. (If by some miracle I run out, I’ll warn you here.)