In the 2 March 2007 issue of the Times Literary Supplement, Patrick McCaughey pans William S. McFeely’s new biography of Thomas Eakins, writing that McFeely’s "view of evidence may satisfy the claims of modern American historiography, although I rather doubt it. It certainly makes for bad art history." In particular, McCaughey is dismissive of the evidence that McFeely presents of Eakins’s homosexuality. Or rather, fails to present, according to McCaughey, who accuses McFeely of making his case by mere assertion. In the 29 March 2007 issue of the New York Review of Books, Christopher Benfey is more polite and circumspect but doesn’t seem any more convinced, calling McFeely’s book "impressionistic and elliptical," noting its "odd combination of historical detail and orphic pronouncements," and offering praise of startling modesty: "Some of his hypotheses seem worth pursuing. . . ."

In the 2 March 2007 issue of the Times Literary Supplement, Patrick McCaughey pans William S. McFeely’s new biography of Thomas Eakins, writing that McFeely’s "view of evidence may satisfy the claims of modern American historiography, although I rather doubt it. It certainly makes for bad art history." In particular, McCaughey is dismissive of the evidence that McFeely presents of Eakins’s homosexuality. Or rather, fails to present, according to McCaughey, who accuses McFeely of making his case by mere assertion. In the 29 March 2007 issue of the New York Review of Books, Christopher Benfey is more polite and circumspect but doesn’t seem any more convinced, calling McFeely’s book "impressionistic and elliptical," noting its "odd combination of historical detail and orphic pronouncements," and offering praise of startling modesty: "Some of his hypotheses seem worth pursuing. . . ."

The two reviewers sharply disagree, however, on at least one issue. Both think that Eakins painted himself into The Gross Clinic (above left, 1875, Philadelphia Museum of Art and Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts), the famous painting of a medical professor with blood on his hands, standing heroically beside a patient with a sliced-open leg, in a surgical theater full of students (a painting recently saved from acquisition by the Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton’s Crystal Bridges). But they differ as to where in the painting Eakins’s self-portrait is supposed to be. "Eakins himself crouches in the bottom right-hand corner spattered with blood, holding one of the retractors for the incision," writes McCaughey in the TLS. "Among the students, Eakins has painted a shadowy portrait of himself, dispassionately taking notes," writes Benfey in the NYRB.

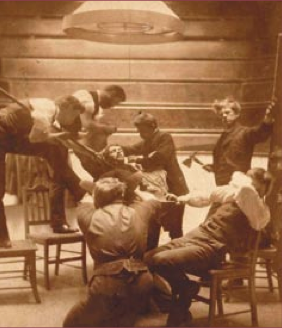

So where’s Thomas? (Since I was too bleary with a head cold to do anything useful this afternoon, I decided to track down the answer in Columbia’s databases.) Eakins and some of his students once posed for a parody (right, c. 1875-79, Woodmere Art Museum) of The Gross Clinic, and in a 1999 article for the journal Representations, art historian Jennifer Doyle wrote of the photograph, "I would like to assert that it is Eakins who poses in the role of the womanly, melodramatic spectator, though I cannot say for certain that it is him." Intriguing as her speculation is, of course, it doesn’t decide the case at hand.

So where’s Thomas? (Since I was too bleary with a head cold to do anything useful this afternoon, I decided to track down the answer in Columbia’s databases.) Eakins and some of his students once posed for a parody (right, c. 1875-79, Woodmere Art Museum) of The Gross Clinic, and in a 1999 article for the journal Representations, art historian Jennifer Doyle wrote of the photograph, "I would like to assert that it is Eakins who poses in the role of the womanly, melodramatic spectator, though I cannot say for certain that it is him." Intriguing as her speculation is, of course, it doesn’t decide the case at hand.

A number of critics have suggested that Eakins is to be seen in the painting as the patient etherized upon the table, or as Dr. Gross, or as both. But this is wandering into interpretation, I’m afraid.

More hardheadedly, in a 1969 article in the Art Bulletin, Gordon Hendricks gave a full list of originals of the painting’s dramatis personae. Hendricks identified the woman in the painting’s left as very likely the patient’s mother, the man in the lower right holding the incision open as Dr. Daniel Appel, the man with the sideburns exploring the wound as Dr. James M. Barton, the holder of the patient’s legs as Dr. Charles S. Briggs, the anesthetist at the patient’s head as Dr. W. Joseph Hearne, and the man writing at the desk to the left of Dr. Gross as Dr. Franklin West. The two shadowy men in the tunnel to the right of Dr. Gross are Hughey the janitor and Dr. S. W. Gross, the central figure’s son. "At right center, looking intently down at the proceedings with pencil and pad, the artist has painted himself," Hendricks concludes. (Hendricks doesn’t identify the patient. He does say, though, that "the operation is for the removal of a sequestrum," a piece of dead bone tissue that forms during chronic inflammation of the bone.)

A description on the website of the painting’s former owner, Thomas Jefferson University, also identifies Eakins as "the first figure seated to the right of the tunnel . . . sketching or writing." In other words, Eakins is the figure about two-thirds of the way up the painting’s right edge, not easy to discern in the reproduction here, or in any reproduction I have at home. It seems as if Benfey is right, and as if the TLS has for once nodded. Whether Eakins was gay, on the other hand, is a controversy I decline to adjudicate this afternoon.

On another note, there didn't seem to be much debate about which one Eakins was in The Swimming Hole 😉