I’ve threatened, at various times, to say unkind words about book design. But I realized recently that it would be better for my karma to say a few kind ones. In fact, there’s a lot of book design that I like, and it isn’t easy to choose which book to praise. It occurred to me that the purest selection would be of a book I haven’t actually read, so that any fondness I might have for content would be neutralized. And I haven’t actually read (not every page, anyway) Henry Glassie’s Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1968), which, according to the back flap of the dust jacket, was designed by someone named Bud Jacobs.

I’ve threatened, at various times, to say unkind words about book design. But I realized recently that it would be better for my karma to say a few kind ones. In fact, there’s a lot of book design that I like, and it isn’t easy to choose which book to praise. It occurred to me that the purest selection would be of a book I haven’t actually read, so that any fondness I might have for content would be neutralized. And I haven’t actually read (not every page, anyway) Henry Glassie’s Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1968), which, according to the back flap of the dust jacket, was designed by someone named Bud Jacobs.

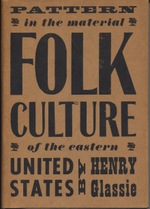

As a rule I’m not wild about typographic covers, but I like this one, because the wood-block lettering nods to the book’s theme of handmade culture and to its time period. You know at once that this is a book about America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and that it’s a little nostalgic, but not fussily so. This is going to be a kind of playful remix. The size of the words corresponds to their importance: in descending order, Folk, Culture, United States, and Pattern. Also, no computer went near this cover. Every letter on it was manifestly kerned by eye and hand.

The page design for Pattern is a scholarly kind of beautiful. It geeks out, and it makes geeking out look lovely. The footnotes are at the feet of the pages, for one thing—not banished to the book’s end. This is important, because the notes are designed, as the author explains in his “Apology and Acknowledgment,” to “provide a loose bibliographical essay.” They’re a kind of anchor to the book’s text, which the author describes as an “impressionistic introduction.” The text meanders, while the footnotes march on, beneath, in an orderly regiment.

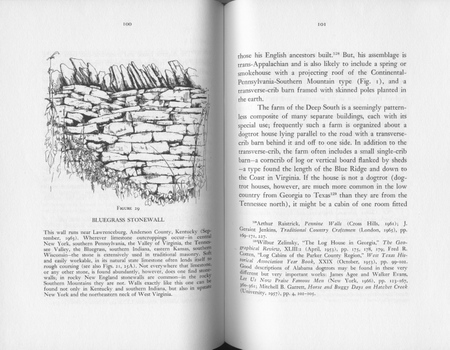

As a third design component, the book has many illustrations, one on nearly every other page, each of which comes with a leisurely caption, which in some cases amounts to a free-standing essay. In the layout above, for example, the caption discusses variations in stone walls, from New England to Kentucky, while the text focuses on the dogtrot house typical of farms in the Deep South, and a footnote directs the reader to descriptions of Alabama dogtrots in Evans and Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, among other sources.

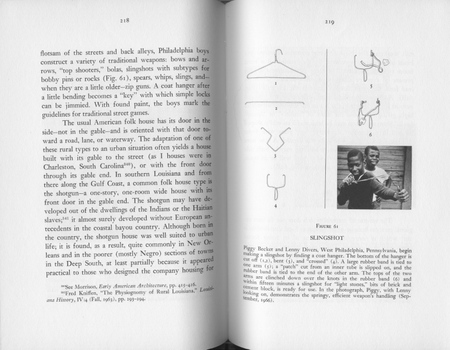

Glassie’s book isn’t merely bibliography and synthesis, however. Some of the information comes from his own field work. He presents a photograph of a rabbit gum, a wooden box trap to catch rabbits. And he prints an interview with a man who used to “sting” fish as a boy; when he saw a fish swimming just under the ice of a creek, he would hit the ice with a mallet to stun the fish beneath, and then cut the ice and take the stunned fish out. An illustration displays the man’s sketch, from memory, of his fish stinging mallet, and a footnote assures the reader that “stinging fish is not a tall tale” by pointing to a similar recollection in print elsewhere. But I’m becoming distracted from pure design, so here’s another layout, which mixes line drawings, a photograph, and a caption to show you how to make a slingshot out of a coathanger, West Philadelphia-style.

There’s an index of fearful completeness, of everything from bacon-grease salad dressing to lobster pots. And one more clever touch worth mentioning, the book’s spine:

It’s a little hard to read, because the technology was no longer really up to spec for machine-made books in 1968, but Bud Jacobs seems to have tried to gild the book’s spine in the style of American books of the mid-nineteenth century. Jacobs stamped the spine with an indicator hand, the book’s title, and the press’s insignia. Back in the day, gilded spines were even more elaborate, in many cases, and the gilding was applied by hand. To the right are a few samples from the 1840s and 1850s, featuring a philanthropess, a waif, and a den of iniquity; a conductor; floral bouquets; the scales of justice; and an all-seeing eye.