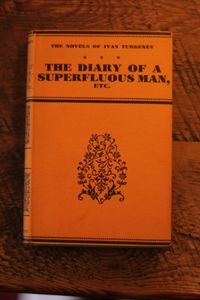

A few weeks ago, after a visit to friends in Garrison, New York, I spotted a sign for a bookstore and made Peter get off the highway. We ended up in a shop called Antipodean Books, where I stayed so long that our plans for that evening were ruined, but where the proprietor, in an act of generosity, offered me thirteen out of the seventeen volumes (what dealers poetically call a "broken set") of the Heinemann edition of Turgenev's complete works (Constance Garnett's translation) for just twenty-five dollars. They are still in their original dust jackets, a fetching, hazardous-materials shade of orange! Since I'd already read a few of Turgenev's better-known titles in other translations, the broken set suited me perfectly. Also, aesthetically speaking, I am weak-willed about duodecimo hardcovers, and each of these is just 4.5 by 6 inches—genuinely pocket-sized. And did I mention the highway-worker's-raincoat orange?

A few weeks ago, after a visit to friends in Garrison, New York, I spotted a sign for a bookstore and made Peter get off the highway. We ended up in a shop called Antipodean Books, where I stayed so long that our plans for that evening were ruined, but where the proprietor, in an act of generosity, offered me thirteen out of the seventeen volumes (what dealers poetically call a "broken set") of the Heinemann edition of Turgenev's complete works (Constance Garnett's translation) for just twenty-five dollars. They are still in their original dust jackets, a fetching, hazardous-materials shade of orange! Since I'd already read a few of Turgenev's better-known titles in other translations, the broken set suited me perfectly. Also, aesthetically speaking, I am weak-willed about duodecimo hardcovers, and each of these is just 4.5 by 6 inches—genuinely pocket-sized. And did I mention the highway-worker's-raincoat orange?

This is by way of bloggy-autobiographical prelude to my point, which is just to present a couple of quotes that I like. The two novels I've read in the set so far are about revolutionaries, but for some reason the passages that have most pleased me in them were about spring.

In Virgin Soil, when the hero Nezhdanov wanders in the garden of his employer one May afternoon, Turgenev writes:

Nezhdanov sat with his back to a thick hedge of young birches, in the dense, soft shade. He thought of nothing; he gave himself up utterly to that peculiar sensation of the spring in which, for young and old alike, there is always an element of pain . . . the restless pain of expectation in the young . . . the settled pain of regret in the old. . . .

I don't have anything to say about the quote, other than that I like the precision and the poignancy of it. (The ellipses are Turgenev's, by the way, not mine.)

The other passage that particularly struck me comes toward the end of On the Eve, a novella about a Bulgarian revolutionary and the Russian woman who falls in love with him, when the hero and heroine find themselves staying in Venice much longer than they intended to and somewhat against their wishes. The Venice chapters come as something as a surprise, a surge of sentiment in a book that has seemed up to that point to be concerned mostly with conflict, and if the book offered no more, they would make it worth the price of admission. The passage seems uncannily to prefigure Thomas Mann, but the bittersweetness is Turgenev's own. Reading it, I discover that my few visits to Italian cities have all taken place in the wrong months, but that's the least of the regrets evoked.

No one who has not seen Venice in April knows all the unutterable fascinations of that magic town. The softness and mildness of spring harmonise with Venice, just as the glaring sun of summer suits the magnificence of Genoa, and as the gold and purple of autumn suits the grand antiquity of Rome. The beauty of Venice, like the spring, touches the soul and moves it to desire; it frets and tortures the inexperienced heart like the promise of a coming bliss, mysterious but not elusive. Everything in it is bright, and everything is wrapt in a drowsy, tangible mist, as it were, of the hush of love; everything in it is so silent and everything in it is kindly; everything in it is feminine, from its name upwards. It has well been given the name of 'the fair city.' Its masses of palaces and churches stand out light and wonderful like the graceful dream of a young god; there is something magical, something strange and bewitching in the greenish-grey light and silken shimmer of the silent water of the canals, in the noiseless gliding of the gondolas, in the absence of the coarse din of a town, the coarse rattling, and crashing, and uproar. 'Venice is dead, Venice is deserted,' her citizens will tell you, but perhaps this last charm—the charm of decay—was not vouchsafed her in the very heyday of the flower and majesty of her beauty. He who has not seen her, knows her not; neither Canaletto nor Guardi (to say nothing of later painters) has been able to convey the silvery tenderness of the atmosphere, the horizon so close, yet so elusive, the divine harmony of exquisite lines and melting colours. One who has outlived his life, who has been crushed by it, should not visit Venice; she will be cruel to him as the memory of unfulfilled dreams of early days; but sweet to one whose strength is at its full, who is conscious of happiness; let him bring his bliss under her enchanted skies; and however bright it may be, Venice will make it more golden with her unfading splendour.

I always thought that some sort of ur-Turgenev scenario would make a nice moody musical. Ambivalent young student type tries to reconcile revolutionary politics and his love for the slightly unattainable smokey-eyed older woman he meets in some bosky grove. Book and lyrics by Tommy Tune. Call it “I’ll Take Turgenev”. Songs that rhyme “arbour” and “ardour” and “Are ya?”. How could it miss?

Twenty-five bucks for 13 highway-worker's-raincoat orange, pocket-sized books by just about anyone, much less Turgenev, is very generous indeed. I may have to stop in to Garrison on my way up to Saratoga later this month…