Five years ago, I denounced deckle edges as an abomination. Before books melt away into ether once and for all, I feel compelled to express another strong opinion about the production of physical books: I hate glue bindings.

I have been gently counseled by book designers that my hatred may not be entirely justified. In fact, they say, there are glue bindings and there are glue bindings. “Hot melt” glues are indeed shoddy, I am told, but some “cold melt” glues are thought to be quite durable if they are applied via “double fan binding,” a process so named because it involves fanning the pages in first one direction, then the other. I hasten to say that all this may be true; I’m no expert. But it doesn’t matter. The trouble with glue bindings is that you never know until it’s too late. At the moment you buy a book bound with glue, it may indeed be more rugged than an identical book sewn together with thread. The question is the integrity of the glue ten years later. Thread lasts, if it’s kept dry and dark. In the Egyptian wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, you can see folded sheets of linen from pharaonic days. Glue, however, often doesn’t last. It’s no help to hear that some glue does. Nowhere in or on a book is there a list of the ingredients of its binding’s glue, and even if there were such a list, only astute chemists would be able to predict longevity from that information.

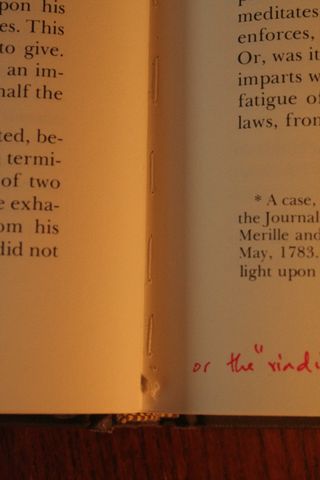

Let me break your heart with some examples. Here is a Northwestern-Newberry paperback of Herman Melville’s Pierre, purchased by your blogger in the mid 1990s, much re-read, and much annotated.

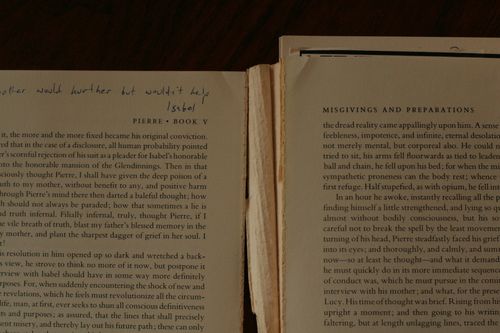

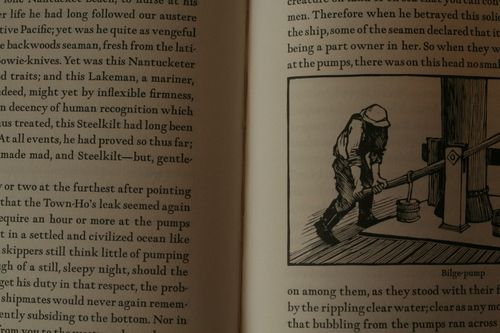

A university press edition! People, they did this to scholars. Not all university presses are so heartless, though. To vindicate them, I include a photo of a University of California Press paperback of Moby-Dick, purchased by your blogger in the late 1980s, also much re-read—though not annotated, because the Barry Moser illustrations made it seem sacrosanct.

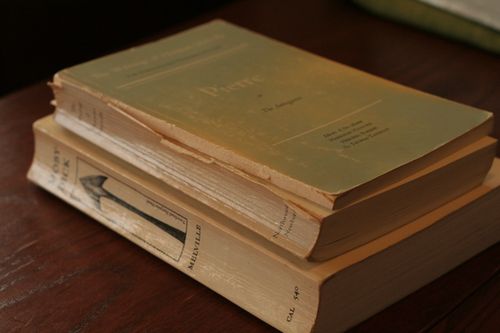

I’ve opened the Moby-Dick to the center of a “gathering,” that is, to the center of a set of pages that were folded together, so if you look closely (after clicking on the picture to expand it), you can see a Morse code of thread running vertically along the fold. (Not all sewing is equal, by the way; the best kind is “sewing through the fold,” also known as “Smyth sewing,” after the brand name of one of the sewing machines capable of doing it.) Though the California paperback is at least five years older, it’s in good shape, and the Northwestern-Newberry is a shambles. For comparison, here’s the latter stacked on the former.

You’re probably thinking, Well, I’m not going to trouble my little head with any of this. I buy hardcovers, after all. Surely they’re sewn not glued. Oh ho, and there you would be wrong. The poet Elizabeth Bishop has been so thoroughly and repeatedly canonized that if I am asked to read one more review solemnly scolding her editors for posthumously printing the fragments found in her desk, I will run screaming into the night. But is the latest of the scolded monumental editions, by her longtime publisher FSG, bound with thread? It is not. (As it happens, though, the mid-1980s FSG hardcovers of Bishop’s collected poetry and prose were glue-bound, too, and seem to be holding up, so maybe FSG uses nice glue, at least with Bishop.)

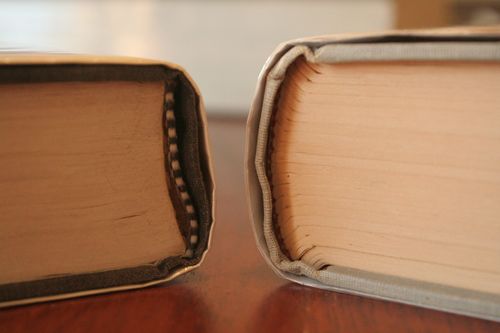

How, those of you whom I have succeeded in making anxious may want to know, can a glued binding be distinguished from a sewn one? On the left, in the photo above, is a glued Philip Roth (Zuckerman Bound, FSG, 1985), and on the right a sewn Henry Roth (Call It Sleep, Pageant, 1960). The little black-and-white skunk-tail-esque ribbon on the Philip Roth is spurious; it’s meant to hearken back to the days when an actual piece of fabric went all the way down the spine interior, and the gatherings were sewn into it, and its presence needn’t imply the existence or absence of any such thing now. What’s indicative is the way the pages meet the spine. In the glued Philip Roth on the left, the pages all run straight into the binding and stop dead. In the sewn Henry Roth on the right, the pages are folded together in gatherings, and they meet the spine in distinct bunches, which look a little like the illustrations of stomach villi from my high school biology textbook.

For further reference, here are the tragic Melville paperbacks again, glue on top, sewing beneath.

So nothing ever goes wrong with a sewn binding? Well, no, sometimes things do go wrong, but when they do, you can fix them yourself. To my dismay, I once discovered that the thread hadn’t passed through a signature or two of pages in my Kent State University Press hardcover of Charles Brockden Brown’s Wieland. I therefore sewed the pages to their neighbors.

So nothing ever goes wrong with a sewn binding? Well, no, sometimes things do go wrong, but when they do, you can fix them yourself. To my dismay, I once discovered that the thread hadn’t passed through a signature or two of pages in my Kent State University Press hardcover of Charles Brockden Brown’s Wieland. I therefore sewed the pages to their neighbors.

More alarmingly, I was three-quarters of the way through marking up a Library of America edition of Howells when I found that a number of pages had been omitted altogether. I found them in a database, printed them out, and sewed them in, too—not as elegantly as I did with Brown, I’m afraid.

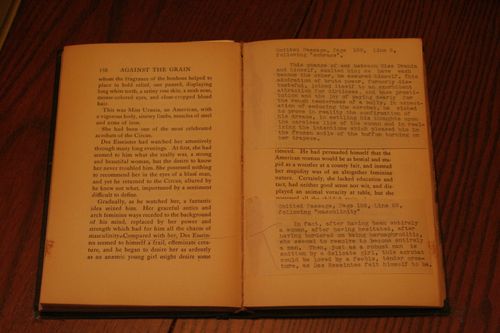

If pressed, I suppose I can bring myself to admit that these book repairs could have been done with glue, and that all I’m saying is that I’m more comfortable with needle and thread. In the interest of objectivity, in fact, I will will conclude with one more photo, of a 1922 translation of J. K. Huysmans’s Against the Grain whose previous owner “completed” it by pasting in slips of onionskin typing paper containing the passages omitted from the English translation. The glue he used has for the most part held up. (The book itself of course has a sewn binding.)

Awesome. I love this post, and your affection for this particular media. Now I know, thread – not glue. And people say the internet is making books extinct.

So just a day after reading this I ran across the hardcover Newberry edition of Pierre at a local used bookshop. The book was still in its shrinkwrap, and so it wasn't immediately apparent whether the binding was glue or thread. Curious, I bought it; sure enough, the binding is glued, and although the gilt spine appears designed to emulate better-quality scholarly editions, even the boards feel pretty shoddy. Hopefully the text and critical apparatus will prove worth the price.

That's awful! As it happens, I bought a used Northwestern-Newberry Pierre in hardcover at a bookstore a couple of weeks ago, to replace the busted paperback. I checked first, to make sure it had a sewn binding. (Your comment struck fear into my heart, so I pulled it off the shelf just now and double-checked.) Your news suggests that some of the NN hardcover Melville are glued and some are sewn—and that trying to figure out which is which, from online booksellers, will be a vexed undertaking. Alas! My NN sewn hardcover Pierre says 1971 on the title page but gives no indication on the copyright page of which printing it is, so I'm guessing it was a first printing. The boards are black and quite sturdy; the spine is decorated in red and gilt. Maybe Northwestern has started to sell glue-bound print-on-demand pseudo-hardcovers to libraries who need to replace missing volumes?