“City Limits,” my review-essay about a white supremacist coup that took place in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898, is published in the 27 April 2020 issue of The New Yorker. The online title is “What a White-Supremacist Coup Looks Like.”

What follows is a bibliographic supplement, crediting some of the sources I drew on. It probably won’t make much sense unless you read the review itself first!

As always, my first debt is to the book under review, David Zucchino’s Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy, published by Atlantic Monthly Press. It’s the capstone to more than a century of attempts to bring the coup into America’s consciousness.

As I mention in my article, two of the earliest such attempts were novels by African Americans. Hanover; or, the Persecution of the Lowly was written by David Bryant Fulton, under the pen-name Jack Thorne, and was published in 1900. There’s an electronic text in the online archive Documenting the American South, though I found the scan in the Internet Archive easier to make sense of. (By the way, I’m mad at the Internet Archive right now for using the pandemic as a pretext for giving away the copyright of living authors, even though I appreciate their hosting of scans of 120-year-old books.) Hanover is a fascinating but unstable text. It opens by reprinting an Associated Press news story, and Fulton doesn’t seem to have been able to decide whether he wanted his book to be fiction or non-fiction. Sometimes a person appears in one chapter as himself, under his real name, and in another as a fictional character, under a pseudonym.

Intriguing side note #1: Fulton up-ends the late-19th-century literary conventions for dialect: uneducated black characters speak in dialect, as they often do in novels of the period, but so do some uneducated white ones. “Who ish mine frients?” asks a German grocer, for example, who, as it happens, sides with the blacks in Wilmington, since they’re his customers. The racist “poor white” Teck Pervis, who seems to be a fictionalized version of the real-life white supremacist Mike Dowling, is given a gerbilly, nasal way of speaking that reminded me of the satire of “white voice” in the recent movies Blackkklansman and Sorry to Bother You. Intriguing side note #2: Fulton hints that there’s something unorthodox about the gender identity of one of his characters, Uncle Guy, a dancer and clarinet soloist in a shoo-fly band that used to play during the black post-Christmas holiday known as Jonkonnu: “he was the embodiment of neatness, feminine in build—it seemed that nature intended to form a woman instead of a man,” Fulton writes.

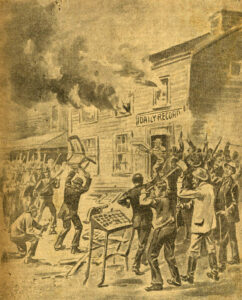

The second novel about Wilmington in 1898, Charles W. Chesnutt’s novel about Wilmington, The Marrow of Tradition, published in 1901, is better known today. There’s a Library of America volume for Chesnutt, and the Norton edition of Marrow has a great historical supplement in back. Chesnutt’s book has a more conventional novelistic shape and heft. It may conform a little too well to convention; the creaking is audible as the machinery of the love-plot grinds forward, and a child in peril is introduced to force the reconciliation of people who in real life would probably have been irreconcilable. Like Fulton, Chesnutt is at pains to give an accurate representation about the outrage that enveloped the Daily Record, the African American newspaper in Wilmington, after its editor, Alex Manly, breached taboo by writing about white women’s sexuality. In fact, sexual purity wasn’t the point, Chesnutt writes: “A peg was needed upon which to hang a coup d’état.” Instead of attempting a full representation of the racial violence that broke out in the city, Chesnutt draws an em dash and makes an aposiopesis: after noting that on the day of the massacre, armed whites challenged and searched every black they met on the street, he writes, “If he resisted any demand of those who halted him—but the records of the day are historical.” There are too many scholarly articles about Chesnutt to list here! Richard Yarborough compares Fulton’s and Chesnutt’s fictionalizations (and provides keys that identify the real-life figures behind the characters) in a chapter titled “Violence, Manhood, and Black Heroism,” in David S. Cecelski and Timothy B. Tyson, eds., Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 and Its Legacy (University of North Carolina, 1998).

The second novel about Wilmington in 1898, Charles W. Chesnutt’s novel about Wilmington, The Marrow of Tradition, published in 1901, is better known today. There’s a Library of America volume for Chesnutt, and the Norton edition of Marrow has a great historical supplement in back. Chesnutt’s book has a more conventional novelistic shape and heft. It may conform a little too well to convention; the creaking is audible as the machinery of the love-plot grinds forward, and a child in peril is introduced to force the reconciliation of people who in real life would probably have been irreconcilable. Like Fulton, Chesnutt is at pains to give an accurate representation about the outrage that enveloped the Daily Record, the African American newspaper in Wilmington, after its editor, Alex Manly, breached taboo by writing about white women’s sexuality. In fact, sexual purity wasn’t the point, Chesnutt writes: “A peg was needed upon which to hang a coup d’état.” Instead of attempting a full representation of the racial violence that broke out in the city, Chesnutt draws an em dash and makes an aposiopesis: after noting that on the day of the massacre, armed whites challenged and searched every black they met on the street, he writes, “If he resisted any demand of those who halted him—but the records of the day are historical.” There are too many scholarly articles about Chesnutt to list here! Richard Yarborough compares Fulton’s and Chesnutt’s fictionalizations (and provides keys that identify the real-life figures behind the characters) in a chapter titled “Violence, Manhood, and Black Heroism,” in David S. Cecelski and Timothy B. Tyson, eds., Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 and Its Legacy (University of North Carolina, 1998).

As I note in my article, the third book-length fictionalization of the coup was a white supremacist one, Thomas Dixon Jr.’s The Leopard’s Spots, published in 1902. It’s best-seller garbage, not to put to fine a point on it—a pure indulgence of resentment and grandiosity. Here’s a solid if dated article about it: Maxwell Bloomfield, “The Leopard’s Spots: A Study in Popular Racism,” American Quarterly 16 (1964): 387–401.

I’m going to jump ahead now to the scholars and other writers who recovered the historical memory. In The Negro and Fusion Politics in North Carolina, 1894–1901, published by the University of North Carolina Press in 1951, Helen G. Edmonds comes across as a patient, commonsensical person with a sly sense of humor; a reader imagines her armed with a small pick, chipping away steadily at white supremacist gunk that has hardened over the facts. In We Have Taken a City: Wilmington Racial Massacre and Coup of 1898, published by Fairleigh Dickinson Press in 1984, H. Leon Prather Sr. painted the conflict in brighter colors and with a looser hand, perhaps because he was writing after the civil rights movement. (Prather’s book seems to be out of print, but you can find used copies pretty easily.) There are a number of useful essays in the Democracy Betrayed anthology mentioned just above, especially Glenda E. Gilmore’s “Murder, Memory, and the Flight of the Incubus” and Michael Honey’s “Class, Race, and Power in the New South.” I’ve come to believe that for every important historical subject, there’s an indispensable dissertation that should have become an acclaimed book but for some reason never did. In this case, that dissertation is Jerome A. McDuffie’s “Politics in Wilmington and New Hanover County, North Carolina, 1865–1900: The Genesis of a Race Riot,” written for his 1979 degree at Kent State University. The novelist Philip Gerard reimagined the coup and massacre in his 1994 novel Cape Fear Rising (John F. Blair). In an essay titled “Revising the Revisionists,” published on the website the Rumpus, Gerard was interviewed about the role that his novel played in Wilmington’s recovery of its historical memory. The interviewer was one of his students, the novelist Johannes Lichtman (disclosure: a friend, after I raved about his novel Such Good Work in a newsletter last year). Gerard himself wrote about his research process and the ethical questions he wrestled with in “The Novelist of History: Using the Techniques of Fiction to Illuminate the Past,” North Carolina Literary Review, 2015. The original 2006 report of North Carolina’s official investigation into the coup is available for download; LeRae Sikes Umfleet streamlined and revised this report into the 2009 book A Day of Blood: The 1898 Wilmington Race Riot, published by the North Carolina Office of Archives and History. It’s copiously illustrated with maps and photos. Don’t be thrown by the format, which makes it look like a high school social studies workbook; it’s perhaps the most thorough treatment of the coup, even if Zucchino’s has a bit more narrative zing. Not long after North Carolina’s report was released in 2006, the Raleigh News & Observer published a reckoning with its own legacy of participation in the ordeal, “The Ghosts of 1898,” by Timothy B. Tyson.

I’m going to jump ahead now to the scholars and other writers who recovered the historical memory. In The Negro and Fusion Politics in North Carolina, 1894–1901, published by the University of North Carolina Press in 1951, Helen G. Edmonds comes across as a patient, commonsensical person with a sly sense of humor; a reader imagines her armed with a small pick, chipping away steadily at white supremacist gunk that has hardened over the facts. In We Have Taken a City: Wilmington Racial Massacre and Coup of 1898, published by Fairleigh Dickinson Press in 1984, H. Leon Prather Sr. painted the conflict in brighter colors and with a looser hand, perhaps because he was writing after the civil rights movement. (Prather’s book seems to be out of print, but you can find used copies pretty easily.) There are a number of useful essays in the Democracy Betrayed anthology mentioned just above, especially Glenda E. Gilmore’s “Murder, Memory, and the Flight of the Incubus” and Michael Honey’s “Class, Race, and Power in the New South.” I’ve come to believe that for every important historical subject, there’s an indispensable dissertation that should have become an acclaimed book but for some reason never did. In this case, that dissertation is Jerome A. McDuffie’s “Politics in Wilmington and New Hanover County, North Carolina, 1865–1900: The Genesis of a Race Riot,” written for his 1979 degree at Kent State University. The novelist Philip Gerard reimagined the coup and massacre in his 1994 novel Cape Fear Rising (John F. Blair). In an essay titled “Revising the Revisionists,” published on the website the Rumpus, Gerard was interviewed about the role that his novel played in Wilmington’s recovery of its historical memory. The interviewer was one of his students, the novelist Johannes Lichtman (disclosure: a friend, after I raved about his novel Such Good Work in a newsletter last year). Gerard himself wrote about his research process and the ethical questions he wrestled with in “The Novelist of History: Using the Techniques of Fiction to Illuminate the Past,” North Carolina Literary Review, 2015. The original 2006 report of North Carolina’s official investigation into the coup is available for download; LeRae Sikes Umfleet streamlined and revised this report into the 2009 book A Day of Blood: The 1898 Wilmington Race Riot, published by the North Carolina Office of Archives and History. It’s copiously illustrated with maps and photos. Don’t be thrown by the format, which makes it look like a high school social studies workbook; it’s perhaps the most thorough treatment of the coup, even if Zucchino’s has a bit more narrative zing. Not long after North Carolina’s report was released in 2006, the Raleigh News & Observer published a reckoning with its own legacy of participation in the ordeal, “The Ghosts of 1898,” by Timothy B. Tyson.

A number of the primary sources unearthed by these scholars are now available online, thanks to several web projects. In 2007, the curator Nicholas Graham published “The 1898 Election in North Carolina,” an online exhibition for the University of North Carolina libraries, where you can find, for example, the Democratic Handbook 1898, which put in writing the party’s white supremacist platform that year, and racist political cartoons by Norman E. Jennett, also known as Sampson Huckleberry, that Josephus Daniels published in the Raleigh News & Observer, including the one of a black vampire that I mention in my article. For more on the cartoons, see Andrea Meryl Kirshenbaum’s article “The Vampire That Hovers Over North Carolina: Gender, White Supremacy, and the Wilmington Race Riot of 1898,” Southern Cultures (1998), and

Rachel Marie-Crane Williams’s ” A War in Black and White: The Cartoons of Norman Ethre Jennett & the North Carolina Election of 1898,” Southern Cultures (2013).

A number of the primary sources unearthed by these scholars are now available online, thanks to several web projects. In 2007, the curator Nicholas Graham published “The 1898 Election in North Carolina,” an online exhibition for the University of North Carolina libraries, where you can find, for example, the Democratic Handbook 1898, which put in writing the party’s white supremacist platform that year, and racist political cartoons by Norman E. Jennett, also known as Sampson Huckleberry, that Josephus Daniels published in the Raleigh News & Observer, including the one of a black vampire that I mention in my article. For more on the cartoons, see Andrea Meryl Kirshenbaum’s article “The Vampire That Hovers Over North Carolina: Gender, White Supremacy, and the Wilmington Race Riot of 1898,” Southern Cultures (1998), and

Rachel Marie-Crane Williams’s ” A War in Black and White: The Cartoons of Norman Ethre Jennett & the North Carolina Election of 1898,” Southern Cultures (2013).

Also in 2007, Karin L. Zipf put together the website “Politics of a Massacre: Discovering Wilmington 1898,” hosted by East Carolina University, where you can find in the bibliography section a scan of “The Story of the Wilmington Rebellion,” the perhaps somewhat inadvertently revealing pamphlet that the volunteer white supremacist historian Harry Hayden self-published in 1936, as well as a 1954 typescript by Hayden titled “The Wilmington Light Infantry Memorial,” about the state guard troops involved in the massacre and coup (the site’s internal link to Hayden’s history of the W.L.I. is broken, so use my link here). Zipf’s site also links to “A Statement of Facts Concerning the Bloody Riot in Wilmington, N. C. Of Interest to Every Citizen of the United States,” the Baptist preacher J. Allen Kirk’s narrative of hiding his wife and niece in a cemetery after the massacre and dodging lynchers as he fled Wilmington by train (though the text is hosted by UNC’s Documenting the American South).

In 2012, the Cape Fear Museum of Science and History shared on Flickr a set of images related to the Wilmington coup, including a four-page letter that Caroline “Carrie” Sadgwar Manly, widow of the Daily Record newspaper editor Alexander Manly, wrote to her children in 1954, describing how her late husband escaped from Wilmington after white supremacists made one of his editorials the pretext for a massacre. The museum later shared on its own website a scrapbook of newspaper clippings given by the Manly family.

A couple of other primary sources: I quote a Democratic newspaperman who recalled in his memoirs that the whites in Wilmington had prepared for the coup six to twelve months prior to pulling it off. His name was Thomas Clawson, and the typescript of his memoir is available in the online finding aid to his papers at the University of North Carolina. I also quote a Populist who joked that everyone believed the rumors of a black uprising except those who invented it; his name was Benjamin F. Keith, and his memoirs, published in 1922, are online at the Internet Archive.

Between 2015 and 2019, the Third Person Project, founded by the writers and history buffs John Jeremiah Sullivan, Joel Finsel, and Trey Morehouse, recruited a group of eighth graders to track down as many surviving copies of Manly’s Daily Record as they could find. Thanks to their detective work, seven issues are now online at the website Digital NC, which is hosted by the Cape Fear Museum, UNC–Chapel Hill, and the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. The Third Person Project went on to hunt through other surviving 19th-century newspapers for articles and squibs that had been reprinted from Manly’s Daily, and then put together what they call a “Remnants Issue” of these shored-up fragments. Sullivan (disclosure: another friend, in this case of long standing) also wrote about the Wilmington coup in his recent New Yorker profile of the folk singer Rhiannon Giddens.

Last but not least, the story of the revival of awareness of the coup and massacre in Wilmington today is traced by Lichtman in the article linked above, and also in Melton Alonza McLaurin’s article “Commemorating Wilmington’s Racial Violence of 1898: From Individual to Collective Memory,” Southern Cultures (2000).