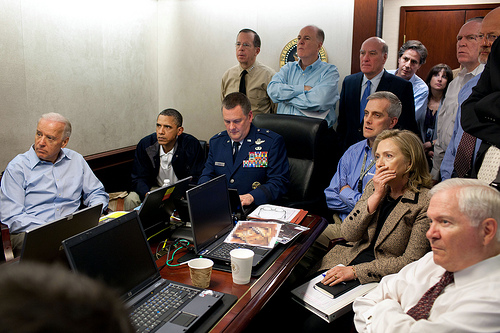

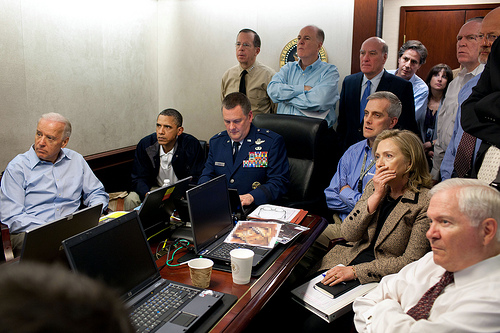

The American government has released a photograph taken on Sunday of President Obama, Vice President Biden, Secretary of State Clinton, Defense Secretary Gates, and other high-ranking officials sitting in the White House’s Situation Room. According to the government-authored caption, the officials are shown receiving “an update on the mission against Osama bin Laden.” The fixity of their attention, however, suggests that the word “update” is an understatement. Almost certainly they were watching moving images on a screen. The New York Times has reported that “The president and his advisers watched Leon E. Panetta, the C.I.A. director, on a video screen, narrating from his agency’s headquarters across the Potomac River what was happening in faraway Pakistan.” An early report, however, claimed that Obama was able to watch a live video feed of the attack, and there has been speculation, without evidence, that such a feed might have come from a camera mounted on the helmet of one of the Navy Seals involved. When PBS asked Panetta himself what the people in the Situation Room were seeing, he gave an equivocal answer, denying that Obama and his team were able to see the shots fired at Bin Laden, but admitting that “I think they were viewing some of the real-time aspects of this as well in terms of the intelligence that we were getting.” Since so many details of the killing have been revised by the government in the past forty-eight hours, and since there are as yet no sources other than the government itself, the safest thing to say is we don’t know what was on the screen, except through what we can see reflected in the watchers’ faces.

At a minimum, then, the people in the Situation Room were watching Panetta describe in real time how three men and one woman were shot. “This was a kill operation,” an official has told Reuters. In its newly released “Narrative of Events,” the Department of Defense now admits that Bin Laden was unarmed and that Bin Laden did not use a woman as a human shield, despite earlier government claims to the contrary. The shootings were probably at close range. “The encounter with bin Laden,” Politico reports, “ended with a kill shot to his face,” and White House spokesperson Jay Carney says that the photograph of Bin Laden taken by the Seals is so “gruesome” that the White House is hesitating to release it. ABC News writes of the photograph that “The insides of his head are visible.”

Photography of the killed seems to be standard operating procedure these days for American special forces. (When the American Raymond A. Davis was arrested in Lahore in February for having shot two Pakistanis, he claimed to be a consular official defending himself against a robbery attempt. A consular official who, after shooting two men through his windshield, got out of his car and photographed the corpses with his digital camera? Davis turned out, of course, to be a CIA security officer.) Perhaps such a photograph of Bin Laden was being displayed on the screen in the Situation Room at the moment that the picture was taken.

A book could probably be written about the expressions in the photograph. It’s possible to download a 1.6-megabyte version; the ambivalences of its revelations become even finer upon magnification. At first, for example, I thought that the look on Gates’s face was one of pride and satisfaction, maybe even smugness. Heh heh, Gates seemed to be saying; this is going well. But in an enlargement of the photo, it is possible to see fear in the outer, lower corners of his eyes, anxiety in the set of his chin, and sorrow in the sagging corner of his mouth. What I at first mistook for smugness turns out, on a closer look, to be a mask of confidence. He’s a warrior; he’s not supposed to mind what he’s looking at; he’s supposed to convey to his subordinates that the violence of war is necessary and lawful. But even he doesn’t like to look at such an image, whatever it is, despite having seen images like it before.

A book could probably be written about the expressions in the photograph. It’s possible to download a 1.6-megabyte version; the ambivalences of its revelations become even finer upon magnification. At first, for example, I thought that the look on Gates’s face was one of pride and satisfaction, maybe even smugness. Heh heh, Gates seemed to be saying; this is going well. But in an enlargement of the photo, it is possible to see fear in the outer, lower corners of his eyes, anxiety in the set of his chin, and sorrow in the sagging corner of his mouth. What I at first mistook for smugness turns out, on a closer look, to be a mask of confidence. He’s a warrior; he’s not supposed to mind what he’s looking at; he’s supposed to convey to his subordinates that the violence of war is necessary and lawful. But even he doesn’t like to look at such an image, whatever it is, despite having seen images like it before.

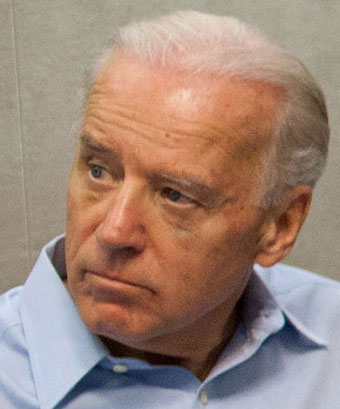

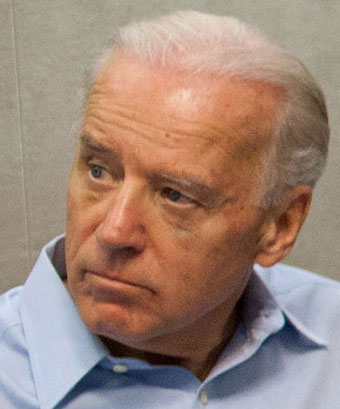

Biden’s face has a similar ambiguity. His left eyelid droops; he’s tired. He has widened his eyes in compensation, making an effort to look alert. Probably in order to reassure others, he’s also making an effort to look as if he’s equal to what he’s seeing—as if it’s all right that the leaders of America are watching a killing in which they are complicit. It is probably legal, he may be telling himself. By any definition, Osama Bin Laden is an enemy of the United States, actively plotting its harm. Perhaps Biden is reminding himself that Harold Koh, a legal adviser to the Obama administration, has justified America’s program of targeted killings abroad as acts of national self-defense. Even the ACLU approves of targeted killings if they take place in a theater of war against an imminent threat. The United States is not at war with Pakistan, but it is at war next door in Afghanistan, and Bin Laden certainly posed an ongoing danger. What’s happening is reasonable, is the thought that Biden seems to be projecting; reason led us here, at any rate.

Biden’s face has a similar ambiguity. His left eyelid droops; he’s tired. He has widened his eyes in compensation, making an effort to look alert. Probably in order to reassure others, he’s also making an effort to look as if he’s equal to what he’s seeing—as if it’s all right that the leaders of America are watching a killing in which they are complicit. It is probably legal, he may be telling himself. By any definition, Osama Bin Laden is an enemy of the United States, actively plotting its harm. Perhaps Biden is reminding himself that Harold Koh, a legal adviser to the Obama administration, has justified America’s program of targeted killings abroad as acts of national self-defense. Even the ACLU approves of targeted killings if they take place in a theater of war against an imminent threat. The United States is not at war with Pakistan, but it is at war next door in Afghanistan, and Bin Laden certainly posed an ongoing danger. What’s happening is reasonable, is the thought that Biden seems to be projecting; reason led us here, at any rate.

Two faces in the picture do not seem composed for view by others. The first is Obama’s. After a glance at it, there can be no question that it is his will driving the mission: the grim mouth, the hungry eyes. There’s an uncanny stillness to Obama’s features. One senses that he has been holding himself in one pose for some time, like a hunter. There is no acceptance in his face. What he is watching is awful to him, too, but he has chosen it. He’s not going to let himself out of any of it. He has to see all of it.

Two faces in the picture do not seem composed for view by others. The first is Obama’s. After a glance at it, there can be no question that it is his will driving the mission: the grim mouth, the hungry eyes. There’s an uncanny stillness to Obama’s features. One senses that he has been holding himself in one pose for some time, like a hunter. There is no acceptance in his face. What he is watching is awful to him, too, but he has chosen it. He’s not going to let himself out of any of it. He has to see all of it.

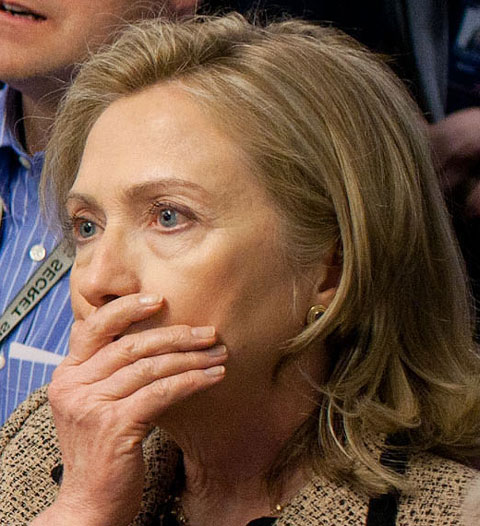

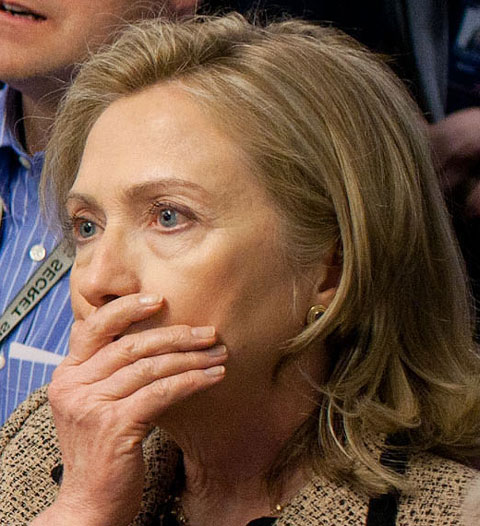

The other naïve face, of course, is that of Hillary Clinton. Her eyes are widened; she has unconsciously covered her mouth with her hand. Her grandmotherly hand. Her expression is one of pure horror. When I first saw this photograph, I thought, Thank God, there was at least one human being in the room. I find the image of her strangely beautiful, even though I’ve never been drawn to her as a politician. It makes me want to cry.

The other naïve face, of course, is that of Hillary Clinton. Her eyes are widened; she has unconsciously covered her mouth with her hand. Her grandmotherly hand. Her expression is one of pure horror. When I first saw this photograph, I thought, Thank God, there was at least one human being in the room. I find the image of her strangely beautiful, even though I’ve never been drawn to her as a politician. It makes me want to cry.

Why shouldn’t I? What else should I do when I see my country’s leaders watching a killing that they have ordered? It is legal for the United States to kill its enemies in war; maybe it’s also legal for us to kill those enemies far from any battlefield, unarmed, in the middle of the night. But America didn’t use to think of itself as the sort of nation that did things that way. Now it is proud of such actions? In his speech on Sunday night, Obama compared the killing of Bin Laden to other triumphs by America:

Tonight, we are once again reminded that America can do whatever we set our mind to. That is the story of our history, whether it’s the pursuit of prosperity for our people, or the struggle for equality for all our citizens; our commitment to stand up for our values abroad, and our sacrifices to make the world a safer place.

Let us remember that we can do these things not just because of wealth or power, but because of who we are.

These words are false. A killing is not comparable to the Apollo space program or the War on Poverty. It is not a moral achievement, let alone a technological one. If the Navy Seals had brought Bin Laden to the United States and we had then put him on trial, that would have been a moral achievement. But a nation need not be a democracy in order to kill its enemies. Revenge is not special. We can take it no matter who we are, and no matter who we become.