My essay “Melville’s Secrets” will be published in the September issue of Leviathan: A Journal of Melville Studies. A subscription to the journal is sent to all members of the Melville Society, so join now (you can use Paypal and do it all online), if you’d like a copy. The essay is a mild revision of the Walter Harding lecture that I gave at SUNY Geneseo in September 2010.

My essay “Melville’s Secrets” will be published in the September issue of Leviathan: A Journal of Melville Studies. A subscription to the journal is sent to all members of the Melville Society, so join now (you can use Paypal and do it all online), if you’d like a copy. The essay is a mild revision of the Walter Harding lecture that I gave at SUNY Geneseo in September 2010.

Category: Nathaniel Hawthorne

Notebook: Tea and Antipathy

"Tea and Antipathy," my review-essay about the dark side of the American Revolution, is published in the December 20 & 27, 2010, issue of The New Yorker. As in the past, I'd like to offer a bibliographic supplement here on my blog. N.B.: This post is more likely to be comprehensible if you first read the article whose sources it describes.

My essay approaches the books under review at a bit of an angle. In As If an Enemy's Country: The British Occupation of Boston and the Origins of Revolution, Richard Archer tells the story of the British occupation of Boston between 1768 and 1770 in a fluently written, chronologically straightforward, somewhat old-fashioned style. He touches on such questions as the revolutionaries' motives and ideological consistency, but he aims mostly at a presentation of the evidence. In American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People, by contrast, T. H. Breen has a thesis to prove. In a style somewhat more rarefied than Archer's, Breen argues that in 1774 and 1775, during the early stages of popular mobilization, America's revolutionaries were more uncouth than we're comfortable remembering today. In his interest in character, Breen is following in the footsteps of historians like Gordon Wood and Joyce Appleby. Archer is aware of the historiographic trend that Breen is participating in, but Archer's is the sort of book that aims to keep to one side of such trends.

In my article, I was adding concerns of my own to Archer's presentation of the facts, and reading Breen's interpretation somewhat against the grain. Breen wants to lift the stigma attached in the modern mind to the insurgent character (though he does retain a few reservations) and is confident that "American insurgents provide no comfort to those in our own time who claim that a single cause or narrow agenda justifies armed violence against neighbors or the state." It isn't clear to me, however, that it's possible to draw that distinction. Insurgents who are confused, misinformed, and paranoid may well believe that they're acting for the sake of a common good—mistakenly—and people with such beliefs today may have more in common with the early revolutionaries than Breen allows. Another distinction between us: Breen believes that consumer culture helped to shape American character in a positive way—see his Marketplace of Revolution (Oxford, 2004)—and I found myself worrying that the corruptions of profit-seeking may have deformed America's political process at the nation's inception.

The third new book mentioned in my article, Defiance of the Patriots, by Benjamin Carp, did not reach me until after I had researched and written most of my essay, and unsurprisingly my essay is somewhat oblique to it as well. The classic and still definitive account of the Boston Tea Party is Benjamin Woods Labaree's The Boston Tea Party (Oxford, 1968). Carp has revisited the events described by Labaree, updating details and uncovering new sources. He is a methodical researcher, who has clearly done his time in the archives; he has found the earliest instance in print of the term "Boston Tea Party" yet known (in 1826, a newspaper quoted a Tea Party participant then living in Ohio as having used the phrase), and his list of participants is no doubt the most accurate yet compiled. Like Archer's, Carp's book is an account rather than an argument; like Breen, however, Carp writes in the contemporary historiographic mode, preferring contextual explanation and characterological description. One chapter places the events of 1773 in the context of the international trade in tea; another, in that of colonists' relations with native Americans; a third, in that of African American slavery. He's not much interested in double-guessing colonists' motives. Indeed, I sometimes felt that Carp was a bit partial to the radicals.

Setting aside for a moment my differences of temperament and perspective from them, however, I should say that I'm indebted to Archer, Breen, and Carp for their many insights and discoveries, as well as for giving me the occasion to discover that I have opinions of my own about the topic. (If you would like to see how Breen himself relates his research to the contemporary Tea Party movement, please see his March 2010 op-ed for the Washington Post.)

The American Revolution is a puzzle unlike other historical puzzles, not least because very few, if any, of those who participated planned for it to happen. Once you start to question professed motives—that is, once you doubt the good faith of some actors and the accuracy of others' understanding of the situation they were in—the puzzle becomes even trickier. A person could spend a lifetime trying to solve it, and so it's with more than the usual trepidation that I offer my online bibliography this time around, conscious that I'll be revealing the limits of my research even more starkly than I usually do, and that the responsible thing for me to do is direct readers to, say, the twelve-page descriptive bibliography at the back of Robert Middlekauff's The Glorious Cause and to the lavish guides to further research that David Hackett Fischer includes at the end of books like Paul Revere's Ride and Washington's Crossing. Now that I've directed you to them and my conscience is clear, here's to the limits within which journalists are obliged to work, and here we go . . .

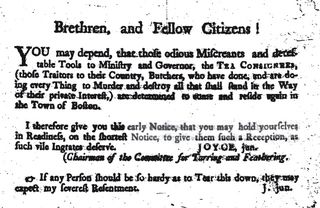

The best account of Joyce, Junior, the mysterious figure who claimed to lead Boston's "Committee for Tarring and Feathering" between 1774 and 1777, is Albert Matthews, "Joyce, Jun.," Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts 8 (1903): 88-104. In a subsequent article, Matthews explained that the pseudonym was probably a reference to Cornet George Joyce, thought by some to have been the executioner of Charles I, though he probably wasn't; see Albert Matthews, "Joyce Jr. Once More," Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts 11 (1906-1907): 280-295. Among the literary critics who have linked Hawthorne's demonic figure to Joyce, Junior, are Roy Harvey Pearce, in "Hawthorne and the Sense of the Past, or, the Immortality of Major Molineux," ELH 21 (1954): 327-349, and Peter Shaw, in "Fathers, Sons, and the Ambiguities of Revolution in 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux,'" New England Quarterly 49 (1976): 559-76. As for the general history of tarring and feathering in America, the best account I found is Benjamin H. Irvin's "Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American Liberties, 1768-1776," New England Quarterly 76 (2003): 197-238, though an older article, R. S. Longley's "Mob Activities in Revolutionary Massachusetts," New England Quarterly 6 (1933): 98-130 was also useful. A disgusted Loyalist once described a lady "so complaisant as to throw her Pillows out of the Window, as the Mob passed," in order to furnish them with feathers. That disgusted Loyalist was Peter Oliver, chief justice of the Superior Court in Massachusetts, whose bitter, intemperate, and pretty funny history of the American Revolution was published in the twentieth century as Peter Oliver's Origin & Progress of the American Revolution: A Tory View, Douglass Adair & John A. Schutz, eds. (The Huntington Library, 1961) and is a sourcebook for patriot human rights violations. The tale of customs agent John Malcom, perhaps the only American to have been tarred and feathered more than once, is best told by his great-great-great-nephew Frank W. C. Hersey, in "Tar and Feathers: The Adventures of Captain John Malcom," Transactions of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts 34 (1941): 429-73 (not digitized, to my knowledge).

The best account of Joyce, Junior, the mysterious figure who claimed to lead Boston's "Committee for Tarring and Feathering" between 1774 and 1777, is Albert Matthews, "Joyce, Jun.," Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts 8 (1903): 88-104. In a subsequent article, Matthews explained that the pseudonym was probably a reference to Cornet George Joyce, thought by some to have been the executioner of Charles I, though he probably wasn't; see Albert Matthews, "Joyce Jr. Once More," Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts 11 (1906-1907): 280-295. Among the literary critics who have linked Hawthorne's demonic figure to Joyce, Junior, are Roy Harvey Pearce, in "Hawthorne and the Sense of the Past, or, the Immortality of Major Molineux," ELH 21 (1954): 327-349, and Peter Shaw, in "Fathers, Sons, and the Ambiguities of Revolution in 'My Kinsman, Major Molineux,'" New England Quarterly 49 (1976): 559-76. As for the general history of tarring and feathering in America, the best account I found is Benjamin H. Irvin's "Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American Liberties, 1768-1776," New England Quarterly 76 (2003): 197-238, though an older article, R. S. Longley's "Mob Activities in Revolutionary Massachusetts," New England Quarterly 6 (1933): 98-130 was also useful. A disgusted Loyalist once described a lady "so complaisant as to throw her Pillows out of the Window, as the Mob passed," in order to furnish them with feathers. That disgusted Loyalist was Peter Oliver, chief justice of the Superior Court in Massachusetts, whose bitter, intemperate, and pretty funny history of the American Revolution was published in the twentieth century as Peter Oliver's Origin & Progress of the American Revolution: A Tory View, Douglass Adair & John A. Schutz, eds. (The Huntington Library, 1961) and is a sourcebook for patriot human rights violations. The tale of customs agent John Malcom, perhaps the only American to have been tarred and feathered more than once, is best told by his great-great-great-nephew Frank W. C. Hersey, in "Tar and Feathers: The Adventures of Captain John Malcom," Transactions of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts 34 (1941): 429-73 (not digitized, to my knowledge).

A wonderful introduction to the historian and Massachusetts governor Thomas Hutchinson is Bernard Bailyn's The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson (Harvard University Press, 1974); it reads like a tragic novel. In a 2004 lecture, Bailyn recalled how, when the book was first published, some critics "said that this biography of a law-and-order conservative who struggled against popular mobs and protestors could only be a disguised defense of Richard Nixon" ("Thomas Hutchinson in Context," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 114 [2006]: 281-300). Many of Hutchinson's writings are available online. His account of his debriefing by George III begins on page 157 of The Diary and Letters of His Excellency Thomas Hutchinson, Esq., Peter Orlando Hutchinson, ed. (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1883). On page 67 of the same book Hutchinson explains that he suspects John Rowe and other merchant-smugglers of having masterminded the destruction of his house. Hutchinson narrates the destruction itself in the third volume of his history of Massachusetts, The History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, from 1749 to 1774 (London: John Murray, 1828), beginning on page 122. When I mention that Hutchinson enjoyed debating political philosophy, I was thinking of his 1773 exchange with the Massachusetts legislature (including John Adams and James Bowdoin) over the nature of the British Parliament's legal authority over the colonies, which Bailyn suggests he indulged in for his own intellectual satisfaction and to his political detriment. The exchange is printed on pages 336 to 396 of Speeches of the Governors of Massachusetts, from 1765 to 1775; and the Answers of the House of Representatives, to the Same (Boston: Russell and Gardner, 1818) and also exists in a modern edition, Briefs of the American Revolution, edited by John Philip Reid (1981).

The destruction of Hutchinson's townhouse was further described by Francis Bernard, then the governor of the colony, in a letter to the earl of Halifax, quoted by Caleb H. Snow in A History of Boston (Boston: Able Bowen, 1825). Edmund S. and Helen M. Morgan give an excellent modern account of this event and the 1760s generally in their classic work The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution (University of North Carolina Press, 1953). Hawthorne rendered the scene in his children's history Grandfather's Chair:

The destruction of Hutchinson's townhouse was further described by Francis Bernard, then the governor of the colony, in a letter to the earl of Halifax, quoted by Caleb H. Snow in A History of Boston (Boston: Able Bowen, 1825). Edmund S. and Helen M. Morgan give an excellent modern account of this event and the 1760s generally in their classic work The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution (University of North Carolina Press, 1953). Hawthorne rendered the scene in his children's history Grandfather's Chair:

The volumes of Hutchinson's library, so precious to a studious man, were torn out of their covers, and the leaves sent flying out of the windows. Manuscripts containing secrets of our country's history, which are now lost forever, were scattered to the wind.

In the same book, Hawthorne also reprinted a letter from Hutchinson describing the riot. You can read the young merchant Henry Bass's admission that his group the Loyal Nine preferred to keep their names hidden behind that of Ebenezer McIntosh in his letter to Samuel P. Savage, 19 December 1765, Savage Papers, Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 44 (1910-1911): 688-689.

The thorny question of economics, smuggling, and corruption is not a new one. Some suspected a link even at the time. "The Plan of the People of Property," General Thomas Gage wrote to the British government in 1765, "has been to raise the lower Class to prevent the Execution of the Law." Writing under the name "Massachusettensis," Daniel Leonard wrote in 1775 that "A smuggler and a whig are cousin Germans, the offspring of two sisters, avarice and ambition. The smuggler received his protection from the Whig, and he in his turn received support from the smuggler." It was the Progressive historians of the early twentieth century who first gave a scholarly formulation to the idea that merchants, eager to protect their smuggling profits and to dodge tax burdens, manipulated popular discontent in the colonies and then lost control of the fire they had set. My starting place was Arthur Meier Schlesinger Sr.'s The Colonial Merchants and the American Revolution, first published in 1918 and revised in 1939. (C. M. Andrews is said to have come up with the same thesis, independent of Schlesinger, and he published his version as "The Boston Merchants and the Non-Importation Movement," Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, vol. 19.) Late in life Schlesinger offered a précis of his argument in "Political Mobs and the American Revolution, 1765-1776," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 99 (1955): 244-50.

Schlesinger's thesis has been regretted by a number of historians as reductive, which is, I suspect, in some quarters a more scholarly-sounding way of calling it unflattering to the American revolutionaries, but his painstaking and lucid book has not been discredited or for that matter surpassed, though in places it has been corrected. (David Ammerman, for example, showed in In the Common Cause: American Response to the Coercive Acts of 1774 [University Press of Virginia, 1974], his classic study of how the colonies' boycotts and protests birthed their self-governance, that Schlesinger was wrong to believe the Pennsylvanian Joseph Galloway's claim that the conservative faction at the First Continental Congress had at any point more than a snowball's chance in hell of dissuading that Congress from declaring a boycott of Great Britain.) Instead of contradicting Schlesinger's thesis, a later generation of historians—including J. G. A. Pocock, Caroline Robbins, Bernard Bailyn, Gordon Wood, and the Morgans, a group who came to be called neo-Whigs—shifted the investigation of revolutionary motive from economics to a more philosophical plane and attempted to understand the mentality of the revolutionaries on their own terms. The neo-Whig historians identified a political ideology with a paranoid streak that they called the eighteenth-century Commonwealthman tradition. In Britain, the tradition was popular among those who were shut out of power during George III's rule and who hearkened back to the English revolutions of 1640 and 1688. Though confined to the radical fringe in Britain, the ideology had a powerful resonance in the American colonies. Why? Bailyn has suggested that it resonated because royally appointed governors had powers in America that kings had lost in Britain a century before. Wood has ingeniously suggested that paranoia was the natural result of combining the Enlightenment insistence that everything can be understood with a new complexity of sociopolitical governance:

At this very moment when the world was outrunning man's capacity to explain it in personal terms, in terms of the passions and schemes of individuals, the most enlightened of the age were priding themselves on their ability to do just that.

Wood surmises that instead of resigning themselves to bafflement over the causes of complex social events, the paranoid thinkers of the late eighteenth century preferred to believe that they had failed to understand because the crucial evidence had been withheld (see Gordon Wood, "Conspiracy and the Paranoid Style: Causality and Deceit in the Eighteenth Century," William and Mary Quarterly 39 [1982]: 402-41).

The neo-Whig angle of vision discovered new riches in American revolutionary history by bringing to life the ideas in its pamphlets, letters, and diaries. The neo-Whig interpretive paradigm became the dominant one in American revolutionary history, and questions of pecuniary interest during the Revolution were set aside not as wrong but as intellectually vulgar. Among historians on the left, who might have been relied upon in other circumstances to doubt and carp, the old Progressive suspicion was not treated any more hospitably, because if Schlesinger and Andrews were right, then the working-class people who had thrown brickbats on behalf of freedom had to be demoted from heroes to pawns. In Crowd Action in Revolutionary Massachusetts, 1765-1780 (Academic Press, 1977), for example, Dirk Hoerder defends the political integrity of lower-class rioters. "Their actions were spontaneous," Hoerder writes, though he admits that "leaders could accentuate issues." Hoerder sees a continuity between the American rioters who launched the Revolution and those who, in the century that led up to it, punished profiteers and adulterers in their communities and menaced religious outsiders who encroached. Hoerder believes that eighteenth-century rioters acted to preserve communal equity, resisting free-market liberalism in favor of a public good that was, alas, to become harder to identify in the next century's proliferation of conflicting private interests. Hoerder's book is a treasury of detail, sometimes overwhelmingly so. His sympathy for the commoner sometimes clouds his judgment—as evidence of Thomas Hutchinson's "arrogance," for example, he confusingly adduces Hutchinson's regret over the unhealthy conditions in a Boston jail—but he is an honest and indefatigable researcher who presents evidence supporting the Progressive thesis as well as that contradicting it. For example, noting that crowd actions against soldiers were conducted in a different manner and spirit during the British occupation of Boston than those against tea importers, Hoerder is willing to wonder if Whig merchants paid for the latter attacks: "The different patterns of action at a time when customary forms of crowd activity were maintained against soldiers suggest that the participants were different, too."

Marc Egnal and Joseph A. Ernst proposed a synthesis of the Progressive thesis and the neo-Whig perspective in their article "An Economic Interpretation of the American Revolution," William and Mary Quarterly 29 (1972): 4-32. The evidence for the Progressive thesis was revisited, and the thesis reconsidered on its own terms, in 1986, when John W. Tyler published Smugglers & Patriots: Boston Merchants and the Advent of the American Revolution (Northeastern U P, 1986). Tyler ended up confirming Schlesinger's work. In fact, Tyler's only significant revision to Schlesinger's storyline was to suggest that in 1774, when radicalism and violence began to frighten moderate merchants, the merchants did not unanimously turn Loyalist but instead split more or less evenly into patriot and loyalist sympathizers. Tyler tells the story of the corrupt customs official Benjamin Barons, whose humiliation, when caught in 1760 trying to suborn an informer, was suspected by Hutchinson to be the ultimate cause of the destruction of Hutchinson's townhouse in 1765. (Barons's tale is told in even greater detail by Maurice Smith in The Writs of Assistance Case [University of California, 1978].) But Tyler's ace card, as a scholar, was his ability to prove from insurance records that certain merchants were indeed smugglers, including such patriots as John Rowe, Solomon Davis, William Molineux, Edward Payne, and William Cooper. In an appendix, Tyler printed a list of Boston merchants, identifying their specialties and naming the known smugglers.

I was convinced by Tyler's book, but I was concerned to note a number of discrepancies in his data. Some of these seem due to sloppiness, though it's hard to know whether the problem was in compiling the data or presenting them. On page 11, for example, Tyler claims to have figured out the specialties of 392 out of 439 Boston merchants; but in Table 4, on page 246, the specialties of only 342 merchants are tallied; and in the appendix, on page 257, there is an analysis of 425 merchants. So how many merchants did Tyler study? On page 30, John Erving is identified as a major smuggler of Dutch goods, but he's not marked as a smuggler in the appendix, where he does appear. These are minor issues, but since Tyler is the only scholar to have dug so deep into the evidence for the Progressive thesis in nearly a century, they suggest to me that the source documents could bear further scrutiny. (Tyler, for his part, does correct an error by Labaree, or rather a misplaced emphasis. Labaree thought that American resistance to the Tea Act of 1773 was driven more by the principle of taxation without representation than by fears of a British monopoly. In fact, Tyler writes, the antimonopoly rhetoric was vital as "the articulation of a genuine fear of the merchants themselves . . . and a propaganda device to divert the consumers' attention from the reduced prices the Tea Act would bring"—an aspect of resistance rhetoric first noticed by Schlesinger.)

Alfred F. Young has supplemented Labaree's definitive account of the Boston Tea Party with The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution (Beacon Press, 1999), which tells the story of how Americans remembered it, or rather, how they declined to for nearly sixty years. Like Hoerder, Young is a person of the left; he considers the Tea Party a radical mass action that helped to change the character of its participants, such as the shoemaker George Robert Twelves Hewes, from deferential to self-respecting. Young's primary texts are two early biographies of Hewes, James Hawkes's A Retrospect of the Boston Tea-Party (S. Bliss, 1834) and Benjamin Bussey Thatcher's Traits of the Tea Party (Harper, 1835), both of which are available online, as is Francis S. Drake's 1884 compilation of primary source documents about the symbolic protest, Tea Leaves. Over at the blog Boston 1775, John L. Bell has looked into the quest to figure out who exactly took part in the Boston Tea Party and has hosted a guest blog-post by Charles Bahne investigating how much the destroyed tea was worth. On the website of the Massachusetts Historical Society , you can read entries in the diary of merchant and documented smuggler John Rowe, who played a highly ambiguous role in the years leading up to the revolution, including Rowe's cautious account of the Tea Party.

Alfred F. Young has supplemented Labaree's definitive account of the Boston Tea Party with The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution (Beacon Press, 1999), which tells the story of how Americans remembered it, or rather, how they declined to for nearly sixty years. Like Hoerder, Young is a person of the left; he considers the Tea Party a radical mass action that helped to change the character of its participants, such as the shoemaker George Robert Twelves Hewes, from deferential to self-respecting. Young's primary texts are two early biographies of Hewes, James Hawkes's A Retrospect of the Boston Tea-Party (S. Bliss, 1834) and Benjamin Bussey Thatcher's Traits of the Tea Party (Harper, 1835), both of which are available online, as is Francis S. Drake's 1884 compilation of primary source documents about the symbolic protest, Tea Leaves. Over at the blog Boston 1775, John L. Bell has looked into the quest to figure out who exactly took part in the Boston Tea Party and has hosted a guest blog-post by Charles Bahne investigating how much the destroyed tea was worth. On the website of the Massachusetts Historical Society , you can read entries in the diary of merchant and documented smuggler John Rowe, who played a highly ambiguous role in the years leading up to the revolution, including Rowe's cautious account of the Tea Party.

How much were the British taxing tea in 1773? The question turns out to be surprisingly difficult to answer. More than a few historians claim that because Parliament in 1767 granted a tax refund of 12 pence a pound on tea imported to Britain if reshipped to America—the same year that the Townshend Acts imposed a new tax of 3 pence a pound—the price of East India Company tea in America actually fell by 9 pence a pound. It turns out that this is a gross simplification, but even at the time many people mistook this gross simplification for the truth, and it got into many history books. The correct, somewhat dizzyingly complex answer is given by Max Farrand in "The Taxation of Tea, 1767–1773," American Historical Review 3 (1898):266–69. The explanation is only three and a half pages long; I have discovered that if you read it out loud three times while taking notes, you eventually understand.

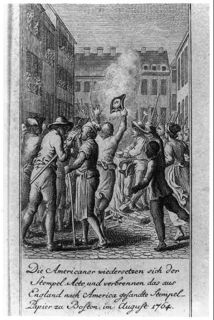

A major source for Breen and for many of the other historians listed here was American Archives, nine mammoth volumes of documentary material from the years 1774 through 1776, compiled and published by the editor Peter Force between 1837 and 1853. All the volumes have been digitized by Northern Illinois University and are searchable, making it easy for a casual reader to dive into the textual sources. (Relatively easy, that is; the search engine is buggy and there's no way to look up a citation if all you have is a volume and page number.) Here is Sam Adams calling the Coercive Acts worse than any tyranny of the Byzantine Empire. Here is the New York City lawyer Gouverneur Morris's satirical comments about Americans as sheep who are about to turn into serpents. Here's a selectman censured for selling a copy of the Continental Association for a pint of flip. Here's a letter that Virginia schoolteacher David Wardrobe wrote to a friend in Scotland about a hanging in effigy, here's his censure as an "enemy to America" for having written it, and here's his attempt at recantation. You may also read original documentation of the drover Jesse Dunbar being carted inside his ox's belly and of a Connecticut doctor named Beebe being tarred and feathered.

A few more scattered sources: The Englishwoman who saw her friends detained on the street in Wilmington, North Carolina, was named Janet Schaw, and her account of their harassment begins on page 191 of the Journal of a Lady of Quality, Being the Narrative of a Journey from Scotland to the West Indies, North Carolina, and Portugal, in the years 1774 to 1776, Evangeline Walker Andrews and Charles McLean Andrews, eds. (Yale, 1921). The author of the pamphlet The Crisis is identified as William Moore by John Sainsbury in Disaffected Patriots: London Supporters of Revolutionary America, 1769-1782 (McGill-Queen's University Press, 1987), confirming a guess made by Paul Leicester Ford in his bibliographic study "The Crisis," The Bibliographer 1 (1902): 139-152. In an article published last year, the scholar Neil York also fingers Moore as the likeliest culprit but notes that in the pages of The Crisis itself "it was emphasized that it was a group effort" (Neil York, "George III, Tyrant: The Crisis as Critic of Empire, History 94 (2009): 434–60).

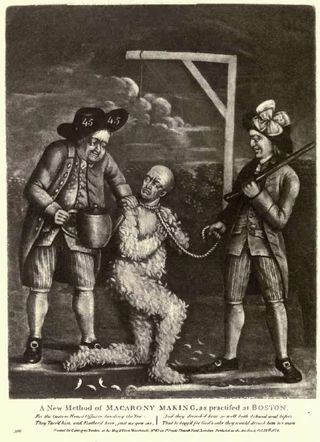

The image at the top of this post, "A New Method of Macarony Making, as practised at Boston in North America," a loose interpretation of John Malcom's fate, was published by Carington Bowles in London in 1774, and is reproduced from page 74 of R. T. H. Halsey's The Boston port bill as pictured by a contemporary London cartoonist (Grolier, 1904). You can see a higher-quality digitization of a smaller version of the same print at the British Museum website, which also owns a hand-colored version. (The British Museum also has a depiction of tarring and feathering by James Gillray, which doesn't actually have anything to do with America at all, but it's by James Gillray, so it's great and who cares.) The Gilder-Lehrman Institute has a colored engraving of the same event by Philip Dawe, with the Boston Tea Party in the background (via). The Massachusetts Historical Society's Coming of the American Revolution site offers a curated tour of a number of original documents from the years leading up to revolution. Please mouse over or click on the other images in this post to find their sources.

Melville’s Secrets: The Walter Harding Lecture, 2010

Yesterday afternoon I gave the 2010 Walter Harding lecture at SUNY Geneseo. The lecture series is named after Walter Harding, who taught for decades in Geneseo and was the preeminent twentieth-century scholar of Henry David Thoreau, and I felt it was a tremendous honor to have been asked. I talked about Melville’s secrets—in particular, about a distorted Platonic myth that I suspect may be present in Moby-Dick. “Ishmael,” I claimed, “might be considered a final, uninvited guest to Plato’s banquet, and his tale a postscript to Diotima’s.”

SUNY Geneseo has already uploaded a video of my talk (perhaps also embedded below, if I’ve coaxed the html sufficiently); a downloadable audio is forthcoming. I’m not going to post a transcript, because I’m hoping to revise the talk into a scholarly paper in the not-too-distant future. To that end, if any of you who heard the talk yesterday or who listen to it online have suggestions, corrections, or comments, please get in touch.

I had a great time at SUNY Geneseo. Many thanks to Marjorie Harding, for the gift that made the lecture series possible; it was an honor to meet the Harding family. I’m very grateful to Geneseo’s English department for their hospitality and great questions. I’m especially grateful to department chair Paul Schacht for his support and guidance, to associate professor Alice Rutkowski for a very kind introduction, and to the college president and English professor Christopher Dahl and his wife Ruth Rowse for a lovely dinner.

Melville’s “Monody”: Probably for Hawthorne

Some time in the last few decades of his life, Herman Melville wrote a short poem, “Monody,” in which a speaker mourns a man whom he loved but became estranged from. In 1929, the critic Lewis Mumford claimed that the poem was an elegy for Hawthorne, who died in 1864. In 1960, the scholar Walter Bezanson strengthened the case by noting that the character Vine in Melville’s epic poem Clarel resembles Hawthorne in many ways, and that the vine-and-grape imagery that surrounds Vine echoes, or is echoed by, an image of a vine and grape in the closing lines of “Monody.” The identification became an established piece of lore among Melville scholars until 1990, when the editor and scholar Harrison Hayford cast doubt on it in “Melville’s ‘Monody’: Really for Hawthorne?” a pamphlet distributed as a keepsake along with the Northwestern-Newberry edition of Clarel, which Hayford co-edited.

I don’t remember when exactly I first read Hayford’s pamphlet, but it was over a decade ago, and I remember that I read it quickly and that it made me angry. Quickly, because although the last chapter of my book American Sympathy, which I must then have been either writing or revising, was concerned with Melville and homosexual eros, it wasn’t much concerned with Melville’s biography. I was hardly averse to his biography—I had drawn on details of Melville’s life in an earlier essay—but one of the ideas I had about American Sympathy was that the book would progress from biography to literature: the first chapter would discuss a set of diaries and letters, and the last would be an interpretation of Billy Budd conducted on a plane of empyrean detachment from the dross of history. It didn’t turn out that neatly, of course, but officially I wasn’t in the market for learning new facts about Melville’s life, so I read quickly. I became angry, because, despite the haste of my reading, it seemed to me that the aim of Hayford’s pamphlet was to bury a piece of the evidence for Melville’s sexuality as manifested in his writing.

Another reason I read quickly was that I wasn’t then in any position fully to evaluate Hayford’s claim, because I couldn’t evaluate Bezanson’s, because I hadn’t yet read Clarel. I shamefacedly report that it is only now, in August of 2010, that I am at last filling this lacuna in my formation as a Melvillean. (More on Clarel another day, perhaps; I seem to have filled a small notebook with notes already, and I’m only two-thirds through the 500-page poem.) In the back of the Northwestern-Newberry edition of Clarel is a version of Hayford’s essay about “Monody,” which abridges Hayford’s argument about the Hawthorne identification but gives a more detailed description of Melville’s manuscript of “Monody,” which survives in Harvard’s Houghton Library. Calmer than I was a decade ago, and also a veteran of journalism, I was impressed, in reading the Clarel version of Hayford’s essay, by his careful use of the available facts—such caution is not always exercised by literary critics. For about ten dollars I bought a copy of his pamphlet from an online bookseller and re-read it last week. I now see that it’s a useful essay, which distinguishes what’s known from what has been speculated, but I don’t think I was entirely wrong in my more emotional reaction a decade ago, because there is something slightly disingenuous about it rhetorically, and it may be worth while to try to spell out why.

“Monody” runs as follows:

To have known him, to have loved him

After loneness long;

And then to be estranged in life,

And neither in the wrong;

And now for death to set his seal—

Ease me, a little ease, my song!By wintry hills his hermit-mound

The sheeted snow-drifts drape,

And houseless there the snow-bird flits

Beneath the fir-tree’s crape:

Glazed now with ice the cloistral vine

That hid the shyest grape.

Hayford points out that no evidence proves that Hawthorne is the object of this poem’s lament, though the mistakes of scholars have sometimes given the impression that such evidence exists. Hayford is assiduous about clearing this scholarly underbrush away. In speculating about the friendship between Hawthorne and Melville, for example, Mumford claimed that Hawthorne’s story “Ethan Brand” depicted Melville, and that Melville was upset by the portrait. In fact, Hayford points out, “Ethan Brand” was published before Melville and Hawthorne ever met.

That’s an obvious blunder, but not all Hayford’s corrections are of errors so black-and-white. Melville and Hawthorne became famously close in 1850 and 1851, while they were not-quite-neighbors in western Massachusetts and while Melville was finishing Moby-Dick. In the fall of 1851, however, Hawthorne abruptly left. Biographer Brenda Wineapple has suggested that Hawthorne wanted to be closer to Boston, to position himself strategically for his friend Franklin Pierce’s 1852 presidential campaign, but some biographers of Melville have speculated that Melville came on too strong, emotionally or perhaps even sexually, and frightened Hawthorne off. If so, then the phrase “estranged in life” in line 3 of “Monody” might point to Hawthorne. Hayford, however, insists quite rightly that Hawthorne and Melville exchanged uniformly warm letters in this period, that Hawthorne’s references to Melville in his letters and journals throughout his life were nothing but kind, and that when Melville visited the Hawthornes in Liverpool in 1856, Hawthorne wrote that “we soon found ourselves on pretty much our former terms of sociability and confidence.” There isn’t “the slightest documentary confirmation,” Hayford writes, of what he calls “the rupture hypothesis.”

To which anyone who’s been around the block might answer: Well, yes and no. When you realize that someone isn’t going to reciprocate your love, you don’t necessarily stop talking to each other. As Robert Milder wrote in “Editing Melville’s Afterlife,” a 1996 review of Hayford’s pamphlet for the journal Text, “‘estrangement’ might . . . imply a slow but perceptible emotional distancing.” In 1852, Melville’s letters to Hawthorne do grow cooler. It’s dangerous to read literature back into biography, but there’s an awful lot of literary evidence pointing to something biographical happening between the two men. In Melville’s Clarel, the hero yearns for Vine, widely thought to represent Hawthorne, imploring him, “Give me thyself!” In Hawthorne’s Blithedale Romance, the narrator rejects the overtures of the burly Hollingsworth, who is often said to represent Melville. And Hawthorne’s 1856 reference to “our former terms of sociability and confidence” is ambiguous: Hawthorne was saying that the 1856 visit went well, but he was also acknowledging that he and Melville were no longer as close as they had been.

When the scholar Jay Leyda printed “Monody” in The Melville Log (1951), a two-volume compilation of documentary sources about Melville, he was so persuaded by the Hawthorne identification that he placed the first stanza of “Monody” below the May 19, 1864 entry for Hawthorne’s death. In Melville’s manuscript, the two stanzas appear on separate pieces of paper, with different inks and different paper, and Leyda thought the second stanza must have been composed later. Hayford, ever a stickler, writes that Leyda was wrong on both counts. Indeed, nothing but speculation linked the dates of the composition of “Monody” and Hawthorne’s death, though Leyda’s reputation for impartiality and documentary style was to convince many scholars otherwise. The different inks and papers of the manuscript proved only that the two stanzas were inscribed at different times, not that they were composed at different times. In fact, Hayford continued, if the stanzas were composed at the same time, as he suspected, then “Monody” couldn’t be about Hawthorne at all, because there couldn’t have been any snow on Hawthorne’s grave in May.

“Hayford’s reasoning is faultless,” Milder wrote in his review,

but it works on the premise that an elegy should have the factual scrupulousness of a newspaper report. . . . No writer who began his career by expanding four weeks of benign captivity among a Marquesan tribe into four months would scruple about introducing snow and ice into an elegy for someone who happened to die in May.

Moreover, there is in fact some reason to believe on the basis of the manuscript that the second stanza was composed later than the first. For one thing, the two stanzas differ markedly in literary style. The first is colloquial, with a phrasing that’s natural and easy; it’s written almost the way someone might talk. The second, however, reverses natural word order. In English, you wouldn’t ordinarily say, “By wintry hills his hermit-mound the sheeted snow-drifts drape.” You would say, “The sheeted snow-drifts drape his hermit-mound by wintry hills.” The contorted syntax and the compression of detail and imagery in the second stanza sound to me like the result of a much more effortful mood.

For another thing, the manuscript contains a telling set of erased alterations to the first stanza, and to the first stanza only. (I’m relying here on Robert C. Ryan’s genetic transcription of the “Monody” manuscript, printed with Hayford’s essay in Clarel). Next to both instances of the word “him” in the first line, Melville pencilled the word “her,” which he then in both instances erased. In Hayford’s words: “Melville considered changing his pronoun references to the mourned person from masculine to feminine.” Hayford concludes from this that the person mourned might therefore have been either a man or a woman, and if we lived in a world with perfect symmetry in that department, Hayford might be right. But we don’t live in such a world, but rather in one in which even Whitman, when printing his poem “Once I Pass’d through a Populous City,” changed

I remember, I say, only one rude and ignorant man, who, when I departed, long and long held me by the hand

to

I remember I say only that woman who passionately clung to me

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that Melville’s lost beloved was a woman. The most likely reason for Melville to change the gender of the pronoun, in that case, would be to hide his love for this woman from his wife. But Melville gave this very manuscript to his wife, to make a clean copy of—her copy of it is printed on the page after his, in the Northwestern-Newberry Clarel—and if the partly erased pencil “her’s” were visible to Hayford and Ryan in 1991, they would surely have been visible to Elizabeth Shaw Melville in the nineteenth century. Another problem: I’ve never heard any biographical hint of Melville having had an affair while married. Yet another: If the woman in question were a lover of Melville’s, it would hardly be true that neither party was “in the wrong,” as the poem has it. Melville would have been a cheating husband, and cheating husbands are proverbially in the wrong. It seems nearly impossible to me that the alterations were an attempt to restore a woman hidden behind Melville’s “his’s.” It seems far more likely that Melville had qualms and briefly considered disguising a romantic poem about a man who had died.

There is, however, no attempted alteration to the word “his” in the first line of the second stanza. That suggests to me that Melville composed the second stanza after his bout of wondering whether to censor the gender of his beloved. If the second stanza was indeed composed later, there’s really no need for its winter imagery to correspond to the May of Hawthorne’s death—though as Milder observes, there’s really no such need in any case.

Hayford never claims that there’s any reason to think that “Monody” isn’t about Hawthorne, and I agree that there’s no final proof that it is. But even if “Monody” isn’t about Hawthorne, the gender of the person mourned reveals that Melville had been deeply moved and upset by the unhappy outcome of his love for another man. Therein, I think, lies Hayford’s rhetorical sleight of hand. Hayford writes as if he believed that if it may be doubted that Melville wrote “Monody” for Hawthorne, then it may also be doubted that Melville grieved because he never got to live out in full his love for another man. But Melville did write “Monody,” and it doesn’t sound to me like the sort of poem written out of feelings that were purely imaginary.

If not Hawthorne, who? It has been suggested, for example by Corey Evan Thompson in a 2006 article for ANQ, that the true subject of “Monody” is Melville’s teenage son Malcolm, who committed suicide in his bedroom in the Melvilles’ New York home on September 11, 1867. This seems far-fetched. Rather clumsily, Thompson argues that Melville couldn’t have longed for Hawthorne to be his close male adult friend because Melville had for a companion Richard Tobias Greene, the man fictionalized as “Toby” in Melville’s first novel Typee. After all, Greene named one of his sons after Melville, Thompson writes. This is true, but even in Typee, Toby isn’t a terribly romantic figure; in the matter of charisma, the cannibals leave him well in the shade. And once returned to America, Greene always lived elsewhere—upstate New York, Ohio, Chicago—and so could hardly have assuaged whatever longings Melville may have had.

More to the point, however, the poem just doesn’t sound like an elegy for a son. The lines “To have known him, to have loved him / After loneness long” are too erotic for a parent to address them to a child, even a dead child. I for one would be much more creeped out by a Melville who wrote such a poem about his son than by a Melville who wrote it about a male friend. If Melville had his son in mind when writing the poem, it’s inexplicable that he considered altering the gender of the poem’s subject—what need for disguise would there be? Melville was said by one of his cousins to have been a strict parent, and he may even have been an abusive one, traits that seem belied by the poem’s claim that “neither [were] in the wrong.” Even if Melville were unconscious of his severity, though, the characterization of the estrangement as equitable seems inconsistent with a parent-child relationship, even one that has gone awry. Nor does the person described resemble what is known about Malcolm. Everyone who knew Hawthorne described him as shy, but according to Hershel Parker, Malcolm’s uncle John Hoadley wrote about the boy’s “playful fondness of children” and his “fondness for social frolicking with his young friends, and acquaintances that he made down town.” Not long before his death, Malcolm joined a volunteer regiment and a baseball team; he hardly seems to have been “the shyest grape.”

In Clarel, however, Vine is addressed with exactly such imagery:

“Ambushed in leaves we spy your grape,”

Cried Derwent [to Vine]; “black but juicy one…”

Vine first appears in the poem at a tomb sculpted with grapes, among other fruit, and is said to have blood like “swart Vesuvian wine” that’s been somehow cooled, as if the imagery of a vine on a grave were with Melville from his first conception of the character.

At the end of his pamphlet, Hayford pronounces over the Hawthorne/”Monody” hypothesis “the Scottish verdict ‘Not Proven.'” True enough, as a matter of biography and history, but the case for Malcolm as the poem’s subject should be thrown out of court. My own verdict is that if the poem’s subject wasn’t Hawthorne, it was a man so like him and so closely linked to him in Melville’s imagination that the distinction between them is, for the purposes of literary interpretation, moot.