At the Paris Review Daily, I reminisce about my pronoun trouble and my fondness for Elizabeth Bishop’s paintings.

Category: painting

Parallels

Yesterday we went to the Gustave Courbet exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was the show’s last day, so it’s not very timely of me to blog about it. But I happened to notice a number of parallels between Courbet and another realist painter, Winslow Homer. (According to Google, real scholars have remarked on the parallels before; I’m just playing amateur here.) Homer was somewhat younger than Courbet and an American. Evidently he went to France just after the Civil War, and he would have encountered Courbet’s work then, but that’s too late, biographically speaking, to explain the parallel that I found most striking, that between Courbet’s The Meeting, or Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet (1854) and Homer’s Prisoners from the Front (1866), which Homer seems to have painted before he left America.

Left: Gustave Courbet, The Meeting, or Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet, 1854, Musée Fabre, Montpellier. Right: Winslow Homer, Prisoners from the Front, 1866, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Courbet painted himself as a virile young wanderer with backback, walking stick, and hat. (There seems to me, by the way, to be something Walt Whitman-esque in Courbet’s early portraits of himself in schlumpy hats, champing on provincial-looking pipes—something of the artist hamming it up as a proletariat, in the days when the revolutionary scent of 1848 still hunt in the air.) The bearded redhead saluting him is his patron, Alfred Bruyas, accompanied by a slouching servant. If Homer did have Courbet’s painting in mind, and perhaps he saw a fellow-artist’s study-sketch of it, or a lithographic reproduction, it’s intriguing that in the patron’s place stands an equally redheaded Confederate soldier, and that the Union soldier who captured him stands in the artist’s. (The superposition brings to mind Henry Ferris, the American painter-hero of William Dean Howells’s 1875 novel A Foregone Conclusion, who enlists in the Union Army at the end of the book.)

The other two parallels I noticed weren’t in composition but merely in subject matter and feeling-tone. First, the ocean:

Left: Gustave Courbet, The Wave, 1869, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Right: Winslow Homer, The Northeaster, 1895, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Second, foxes in snow:

Left: Gustave Courbet, Fox in the Snow, 1860, Dallas Museum of Art. Right: Winslow Homer, Fox Hunt, 1893, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Color of hope

I am the sort of person geeky enough to not only buy but read the little souvenir books published by art museums, so after we saw Benozzo Gozzoli’s fresco cycle The Cavalcade of the Magi (1459-62) in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi last week in Florence, I bought a booklet that promised to reveal the meanings hidden in its princes in gold-embroidered dress and its predatory animals rampant in a Tuscan-like landscape. The three Magi’s color schemes turned out to be easy to explain: Caspar, Balthasar, and Melchior wear white, green, and red respectively because these are the colors of the “theological virtues”: white for faith, green for hope, and red for charity. “Colours are symbols,” writes Lucia Ricciardi, “and as such have multiple significations—sometimes contradictory ones.” (Before I continue the quotation, I should perhaps warn you that I was, in the end, an American tourist, and that I’m going to descend abruptly from early modern symbology into tawdry relevance to the current election cycle.)

Ricciardi again:

There were in fact no entirely ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ colours: it was the combinations and the juxtapositions that established their meaning. Yellow, which in antiquity represented the divine light, retained this positive connotation, and in addition referred to gold; but the combination of yellow and green, for example, suggested treachery, disorder and degeneration—even madness. Since ancient times red had signified strength, courage, love and generosity, but also pride, cruelty and anger, especially—from a certain period—when associated with blue.

So it wouldn’t, from a medieval perspective, be the redness of red America that’s problematic. It’s only the juxtaposition with blue. Perhaps if the Democrats were recoded green, which, by the way, I learned on this trip was thought by Dominican monks to be the most suitable color for the walls of a library.

[Source: Franco Cardini, Lucia Riccardi, and Cristina Acidini Luchinat, The Chapel of the Magi in Palazzo Medici (Florence: Mandragora, 2001).]Where’s Thomas?

In the 2 March 2007 issue of the Times Literary Supplement, Patrick McCaughey pans William S. McFeely’s new biography of Thomas Eakins, writing that McFeely’s "view of evidence may satisfy the claims of modern American historiography, although I rather doubt it. It certainly makes for bad art history." In particular, McCaughey is dismissive of the evidence that McFeely presents of Eakins’s homosexuality. Or rather, fails to present, according to McCaughey, who accuses McFeely of making his case by mere assertion. In the 29 March 2007 issue of the New York Review of Books, Christopher Benfey is more polite and circumspect but doesn’t seem any more convinced, calling McFeely’s book "impressionistic and elliptical," noting its "odd combination of historical detail and orphic pronouncements," and offering praise of startling modesty: "Some of his hypotheses seem worth pursuing. . . ."

In the 2 March 2007 issue of the Times Literary Supplement, Patrick McCaughey pans William S. McFeely’s new biography of Thomas Eakins, writing that McFeely’s "view of evidence may satisfy the claims of modern American historiography, although I rather doubt it. It certainly makes for bad art history." In particular, McCaughey is dismissive of the evidence that McFeely presents of Eakins’s homosexuality. Or rather, fails to present, according to McCaughey, who accuses McFeely of making his case by mere assertion. In the 29 March 2007 issue of the New York Review of Books, Christopher Benfey is more polite and circumspect but doesn’t seem any more convinced, calling McFeely’s book "impressionistic and elliptical," noting its "odd combination of historical detail and orphic pronouncements," and offering praise of startling modesty: "Some of his hypotheses seem worth pursuing. . . ."

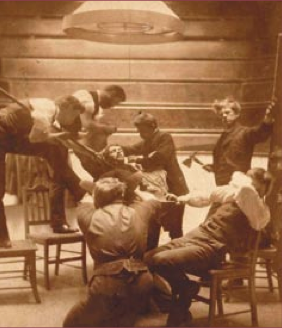

The two reviewers sharply disagree, however, on at least one issue. Both think that Eakins painted himself into The Gross Clinic (above left, 1875, Philadelphia Museum of Art and Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts), the famous painting of a medical professor with blood on his hands, standing heroically beside a patient with a sliced-open leg, in a surgical theater full of students (a painting recently saved from acquisition by the Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton’s Crystal Bridges). But they differ as to where in the painting Eakins’s self-portrait is supposed to be. "Eakins himself crouches in the bottom right-hand corner spattered with blood, holding one of the retractors for the incision," writes McCaughey in the TLS. "Among the students, Eakins has painted a shadowy portrait of himself, dispassionately taking notes," writes Benfey in the NYRB.

So where’s Thomas? (Since I was too bleary with a head cold to do anything useful this afternoon, I decided to track down the answer in Columbia’s databases.) Eakins and some of his students once posed for a parody (right, c. 1875-79, Woodmere Art Museum) of The Gross Clinic, and in a 1999 article for the journal Representations, art historian Jennifer Doyle wrote of the photograph, "I would like to assert that it is Eakins who poses in the role of the womanly, melodramatic spectator, though I cannot say for certain that it is him." Intriguing as her speculation is, of course, it doesn’t decide the case at hand.

So where’s Thomas? (Since I was too bleary with a head cold to do anything useful this afternoon, I decided to track down the answer in Columbia’s databases.) Eakins and some of his students once posed for a parody (right, c. 1875-79, Woodmere Art Museum) of The Gross Clinic, and in a 1999 article for the journal Representations, art historian Jennifer Doyle wrote of the photograph, "I would like to assert that it is Eakins who poses in the role of the womanly, melodramatic spectator, though I cannot say for certain that it is him." Intriguing as her speculation is, of course, it doesn’t decide the case at hand.

A number of critics have suggested that Eakins is to be seen in the painting as the patient etherized upon the table, or as Dr. Gross, or as both. But this is wandering into interpretation, I’m afraid.

More hardheadedly, in a 1969 article in the Art Bulletin, Gordon Hendricks gave a full list of originals of the painting’s dramatis personae. Hendricks identified the woman in the painting’s left as very likely the patient’s mother, the man in the lower right holding the incision open as Dr. Daniel Appel, the man with the sideburns exploring the wound as Dr. James M. Barton, the holder of the patient’s legs as Dr. Charles S. Briggs, the anesthetist at the patient’s head as Dr. W. Joseph Hearne, and the man writing at the desk to the left of Dr. Gross as Dr. Franklin West. The two shadowy men in the tunnel to the right of Dr. Gross are Hughey the janitor and Dr. S. W. Gross, the central figure’s son. "At right center, looking intently down at the proceedings with pencil and pad, the artist has painted himself," Hendricks concludes. (Hendricks doesn’t identify the patient. He does say, though, that "the operation is for the removal of a sequestrum," a piece of dead bone tissue that forms during chronic inflammation of the bone.)

A description on the website of the painting’s former owner, Thomas Jefferson University, also identifies Eakins as "the first figure seated to the right of the tunnel . . . sketching or writing." In other words, Eakins is the figure about two-thirds of the way up the painting’s right edge, not easy to discern in the reproduction here, or in any reproduction I have at home. It seems as if Benfey is right, and as if the TLS has for once nodded. Whether Eakins was gay, on the other hand, is a controversy I decline to adjudicate this afternoon.