In the 22 October 2012 issue of The New Yorker, I review Troy Bickham’s The Weight of Vengeance, a new book about the War of 1812, in an article titled “Unfortunate Events,” as in “a series of.” (Subscription required.)

Category: war

Debtmageddon vs. the robot utopia

It seems likely to me that almost everything prescribed by politicians as a remedy for America’s economic doldrums is wrong. I’m not an economist, so my opinion should probably be taken with a grain of salt. But since reading the news has begun to take on an Alice in Wonderland quality for me, I wanted to try to set down in words how my understanding diverges from theirs.

Just so you know where this is headed: I suspect that the flow of money in America has broken down because wealth is too highly concentrated, and that for at least a generation or so, the government ought to tax the rich heavily and spend on the poor and middle class just as heavily.

Why do all politicians and most pundits recommend the opposite? Flawed metaphors, I think. Most people make a natural comparison between a nation’s budget and a family’s. If a family is sliding into debt, the only remedies are to earn more and spend less. But a nation’s economy is not at all like a family’s. For one thing, within most families, communism prevails: the rule governing money is, From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs. For better or worse, this doesn’t happen to be the rule governing money in America at large. Also, within most families, money is not exchanged for labor. In a pedagogical, largely symbolic way, Jimmy may be given $2 a week in exchange for taking out the garbage. But the person who cooks and cleans does not clock his hours; the children do not buy their dinners. The exchange of labor and goods within a family is for the most part unmeasured and invisible, and it makes more sense to understand a family as a group of people functioning a single economic agent. If the sort of thing that brings a family from debt to prosperity also helps a nation, it’s logical coincidence. Family and nation are so unlike each other that there’s no reason to expect it to.

The nation-family metaphor is nonetheless powerful. Even though most economists believe that reduced government spending will worsen the current recession, almost all politicians have caved into the “common-sense” idea that a nation in economic trouble ought to reduce its debt, leaving Paul Krugman to cry in the wilderness. The metaphor also drives, I suspect, another popular economic idea with almost no empirical support, namely, the notion that instead of taxing the wealthy, the government should reward them, in hopes that the wealth they accumulate will trickle down to others in the nation. The wealthy have proven that they know how to make a profit, this line of reasoning goes; get out of their way and let them make the economy grow.

The notion appeals, I suspect, because it, too, would make sense if a nation were like a family. In fact it’s excellent economic advice for a family. If Mother is a whizbang software engineer and Father’s just a freelance writer, it doesn’t make economic sense to tax them with household chores equally. Father should change more diapers and wash more dishes, freeing up Mother to devote more energy on coding the latest breakthrough app. (Whether this sort of inequity is good for the marriage bed, as well as for the pocketbook, is a different question. But it’s well understood that marriages are economically more than the sum of their parts only when spouses differentiate in their skills and tasks, rather than splitting all responsibilities identically.) If the richest people in a nation were analogous to the primary breadwinners in a family, and if income taxes were analogous to housekeeping chores, then it would make sense for the nation as a whole to indulge the rich in their profit-making and to believe in the existence of the trickle-down fairy. But neither analogy holds. Mother the software engineer, remember, deposits her paycheck every week in the family’s communal bank account; this bank account feeds her freeloading children, not to mention the dog; Mother may even let Father the freelance writer buy a new laptop that his personal earnings don’t yet justify. By contrast, when a corporate executive is given a break on his capital earnings tax, he is thereby exempted from, say, providing food for fellow Americans who can’t earn enough to feed themselves or investing in the future earning potential of a worker who’s not yet up to speed. Yes, he’s now able to make money faster, but the reason that other family members make sacrifices for Mother the software engineer is that they know she’s going to share her wealth—that her wealth is also theirs. The wealth of the little-taxed corporate executive is only his.

Proponents of trickle-downism will argue that the little-taxed corporate executive will in fact share his wealth by spending it, and that his purchase of goods and services will drive economic growth more efficaciously than mere giveaways would. But it turns out that the executive doesn’t spend more, or not enough more for his increased spending to be helpful to the economy—for the simple reason that he doesn’t need to. In the hands of rich people, money moves slowly. That’s what it means to be rich: you have more money than the cost of all the things you need or want. A poor person, by contrast, needs more than he can afford. The poor therefore spend money faster. If you want to boost a nation’s economic growth, it’s better to give to the poor, not the rich. A dollar given to a poor man multiplies faster, Keynes observed, than a dollar given to a rich man.

Economic inequity has been extremely high in the past decade, much as it was in the 1920s and 1930s. The popular understanding of the Great Depression is that it ended because World War II finally obliged American politicians to forget their prudence, and borrow and spend enormous sums. Supposedly this great deficit expenditure stimulated the American economy, like an adrenaline shot. Maybe. But what if the metaphor of stimulation is wrong too? What if it wasn’t the deficit spending of World War II that stimulated the American economy, but the war’s redistribution of wealth? The war obliged America to employ a literal army of people as soldiers and factory workers, and after the war, America felt obliged to continue to reward the working classes with expanded social services, including free higher education for veterans. The period from World War II to the 1970s turned out to be the greatest era of prosperity America has ever known. Is it a coincidence that it followed a massive, government-run redistribution of wealth, which happened to take the form of a war? When TARP and a fiscal stimulus bill were passed a couple of years ago, I remember thinking to myself, well, if the mainstream economists are right, and the problem with America can be remedied by an injection of deficit spending, then my gloom will be disproved. But if my suspicion is right that the underlying problem is economic inequity, then no stimulating injection, however large, will succeed. The economy will be lackluster until something happens that shifts wealth from the rich to the poor. Such a shift is unlikely in today’s political climate, of course. Political power naturally follows wealth, so the rich, owning as they do a disproportionate share of the nation’s wealth, now also control a disproportionate share of its political decisions. In a catch-22, the inequity undermining the economy makes impossible the political action needed to remedy it.

Why haven’t our current wars had the same effect that World War II did? I don’t know. Maybe we’re not paying our soldiers enough; maybe the military’s heavy investment in technology and equipment has muted war’s impact as a redistributor of wealth. (And maybe, of course, I’m wrong. I don’t have the statistical chops to back up this analysis.)

The mention of military technology brings me to my last idea. This is the challenge of the robot utopia. You remember the robot utopia. You imagined it when you were in fifth grade, and your juvenile mind first seized with rapture upon the idea of intelligent machines that would perform dull, repetitive tasks yet demand nothing for themselves. In the future, you foresaw, robots would do more and more, and humans less and less. There would be no need for humans to endanger themselves in coal mines or bore themselves on assembly lines. A few people would always be needed to repair and build the robots, and this drudgery of robot supervision would have to be rewarded somehow, but someday robots would surely make wealth so abundant that most people wouldn’t need to work and would be free merely to enjoy and cultivate themselves—by, say, hunting in the morning, fishing in the afternoon, and doing literary criticism after dinner.

Your fifth-grade self was wrong, of course. Robots aren’t altruistic beings; they’re capital investments; and though robots may not ask to be paid, their owners demand a return on their investment. We now live in the robot utopia, which isn’t one. Thanks in large part to computerized mechanization, manufacturing productivity in the past century has increased many times over. Standards of living are higher than they ever were, but we no longer need as many humans to work as we once did. Perhaps not coincidentally, human wages, in America at least, have stagnated since the 1970s. If humans made no more money in the past four decades, where did the wealth created by the higher productivity go? Toward robot wages, as it were. The owners of the robots took the money—that is, the capitalists. Any fifth-grader can see where this leads. At some point society has to choose. Either society accepts the robots’ gift as a general one, and redistributes the wealth that the robots inadvertently concentrate, or society allows the robots to become the exclusive tools of an ever-shrinking elite, increasingly resented, in confused fashion, by the people whom the robots have displaced.

The robots are here. By now they automate even much of our social lives. You might compare the political challenge they represent to what’s known as the “resource curse”—the infamous difficulty that oil-rich nations have in preserving democracy while sharing the oil’s proceeds. Do we want to be Norway or Saudi Arabia? The choice seems to be between democratic socialism and tyranny. I know my understanding will strike many as implausible, if not unspeakable: I’m saying that the country is suffering economically because it doesn’t know what to do with all its surplus wealth.

Blowup

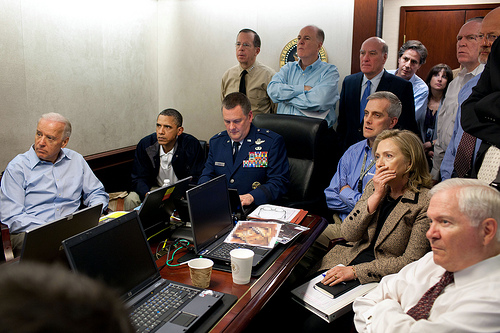

The American government has released a photograph taken on Sunday of President Obama, Vice President Biden, Secretary of State Clinton, Defense Secretary Gates, and other high-ranking officials sitting in the White House’s Situation Room. According to the government-authored caption, the officials are shown receiving “an update on the mission against Osama bin Laden.” The fixity of their attention, however, suggests that the word “update” is an understatement. Almost certainly they were watching moving images on a screen. The New York Times has reported that “The president and his advisers watched Leon E. Panetta, the C.I.A. director, on a video screen, narrating from his agency’s headquarters across the Potomac River what was happening in faraway Pakistan.” An early report, however, claimed that Obama was able to watch a live video feed of the attack, and there has been speculation, without evidence, that such a feed might have come from a camera mounted on the helmet of one of the Navy Seals involved. When PBS asked Panetta himself what the people in the Situation Room were seeing, he gave an equivocal answer, denying that Obama and his team were able to see the shots fired at Bin Laden, but admitting that “I think they were viewing some of the real-time aspects of this as well in terms of the intelligence that we were getting.” Since so many details of the killing have been revised by the government in the past forty-eight hours, and since there are as yet no sources other than the government itself, the safest thing to say is we don’t know what was on the screen, except through what we can see reflected in the watchers’ faces.

At a minimum, then, the people in the Situation Room were watching Panetta describe in real time how three men and one woman were shot. “This was a kill operation,” an official has told Reuters. In its newly released “Narrative of Events,” the Department of Defense now admits that Bin Laden was unarmed and that Bin Laden did not use a woman as a human shield, despite earlier government claims to the contrary. The shootings were probably at close range. “The encounter with bin Laden,” Politico reports, “ended with a kill shot to his face,” and White House spokesperson Jay Carney says that the photograph of Bin Laden taken by the Seals is so “gruesome” that the White House is hesitating to release it. ABC News writes of the photograph that “The insides of his head are visible.”

Photography of the killed seems to be standard operating procedure these days for American special forces. (When the American Raymond A. Davis was arrested in Lahore in February for having shot two Pakistanis, he claimed to be a consular official defending himself against a robbery attempt. A consular official who, after shooting two men through his windshield, got out of his car and photographed the corpses with his digital camera? Davis turned out, of course, to be a CIA security officer.) Perhaps such a photograph of Bin Laden was being displayed on the screen in the Situation Room at the moment that the picture was taken.

A book could probably be written about the expressions in the photograph. It’s possible to download a 1.6-megabyte version; the ambivalences of its revelations become even finer upon magnification. At first, for example, I thought that the look on Gates’s face was one of pride and satisfaction, maybe even smugness. Heh heh, Gates seemed to be saying; this is going well. But in an enlargement of the photo, it is possible to see fear in the outer, lower corners of his eyes, anxiety in the set of his chin, and sorrow in the sagging corner of his mouth. What I at first mistook for smugness turns out, on a closer look, to be a mask of confidence. He’s a warrior; he’s not supposed to mind what he’s looking at; he’s supposed to convey to his subordinates that the violence of war is necessary and lawful. But even he doesn’t like to look at such an image, whatever it is, despite having seen images like it before.

A book could probably be written about the expressions in the photograph. It’s possible to download a 1.6-megabyte version; the ambivalences of its revelations become even finer upon magnification. At first, for example, I thought that the look on Gates’s face was one of pride and satisfaction, maybe even smugness. Heh heh, Gates seemed to be saying; this is going well. But in an enlargement of the photo, it is possible to see fear in the outer, lower corners of his eyes, anxiety in the set of his chin, and sorrow in the sagging corner of his mouth. What I at first mistook for smugness turns out, on a closer look, to be a mask of confidence. He’s a warrior; he’s not supposed to mind what he’s looking at; he’s supposed to convey to his subordinates that the violence of war is necessary and lawful. But even he doesn’t like to look at such an image, whatever it is, despite having seen images like it before.

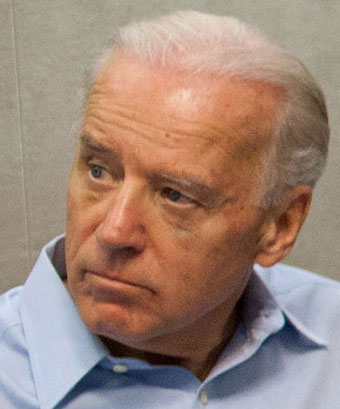

Biden’s face has a similar ambiguity. His left eyelid droops; he’s tired. He has widened his eyes in compensation, making an effort to look alert. Probably in order to reassure others, he’s also making an effort to look as if he’s equal to what he’s seeing—as if it’s all right that the leaders of America are watching a killing in which they are complicit. It is probably legal, he may be telling himself. By any definition, Osama Bin Laden is an enemy of the United States, actively plotting its harm. Perhaps Biden is reminding himself that Harold Koh, a legal adviser to the Obama administration, has justified America’s program of targeted killings abroad as acts of national self-defense. Even the ACLU approves of targeted killings if they take place in a theater of war against an imminent threat. The United States is not at war with Pakistan, but it is at war next door in Afghanistan, and Bin Laden certainly posed an ongoing danger. What’s happening is reasonable, is the thought that Biden seems to be projecting; reason led us here, at any rate.

Biden’s face has a similar ambiguity. His left eyelid droops; he’s tired. He has widened his eyes in compensation, making an effort to look alert. Probably in order to reassure others, he’s also making an effort to look as if he’s equal to what he’s seeing—as if it’s all right that the leaders of America are watching a killing in which they are complicit. It is probably legal, he may be telling himself. By any definition, Osama Bin Laden is an enemy of the United States, actively plotting its harm. Perhaps Biden is reminding himself that Harold Koh, a legal adviser to the Obama administration, has justified America’s program of targeted killings abroad as acts of national self-defense. Even the ACLU approves of targeted killings if they take place in a theater of war against an imminent threat. The United States is not at war with Pakistan, but it is at war next door in Afghanistan, and Bin Laden certainly posed an ongoing danger. What’s happening is reasonable, is the thought that Biden seems to be projecting; reason led us here, at any rate.

Two faces in the picture do not seem composed for view by others. The first is Obama’s. After a glance at it, there can be no question that it is his will driving the mission: the grim mouth, the hungry eyes. There’s an uncanny stillness to Obama’s features. One senses that he has been holding himself in one pose for some time, like a hunter. There is no acceptance in his face. What he is watching is awful to him, too, but he has chosen it. He’s not going to let himself out of any of it. He has to see all of it.

Two faces in the picture do not seem composed for view by others. The first is Obama’s. After a glance at it, there can be no question that it is his will driving the mission: the grim mouth, the hungry eyes. There’s an uncanny stillness to Obama’s features. One senses that he has been holding himself in one pose for some time, like a hunter. There is no acceptance in his face. What he is watching is awful to him, too, but he has chosen it. He’s not going to let himself out of any of it. He has to see all of it.

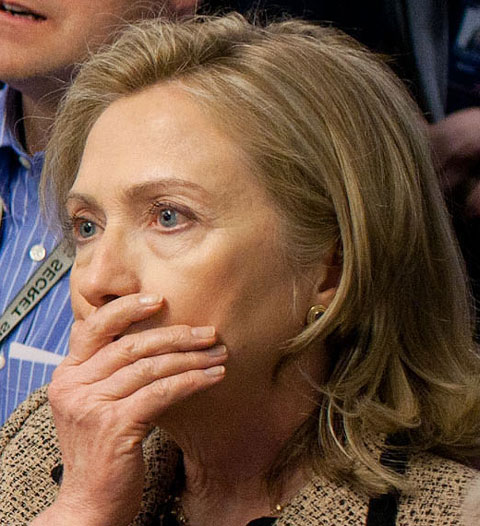

The other naïve face, of course, is that of Hillary Clinton. Her eyes are widened; she has unconsciously covered her mouth with her hand. Her grandmotherly hand. Her expression is one of pure horror. When I first saw this photograph, I thought, Thank God, there was at least one human being in the room. I find the image of her strangely beautiful, even though I’ve never been drawn to her as a politician. It makes me want to cry.

The other naïve face, of course, is that of Hillary Clinton. Her eyes are widened; she has unconsciously covered her mouth with her hand. Her grandmotherly hand. Her expression is one of pure horror. When I first saw this photograph, I thought, Thank God, there was at least one human being in the room. I find the image of her strangely beautiful, even though I’ve never been drawn to her as a politician. It makes me want to cry.

Why shouldn’t I? What else should I do when I see my country’s leaders watching a killing that they have ordered? It is legal for the United States to kill its enemies in war; maybe it’s also legal for us to kill those enemies far from any battlefield, unarmed, in the middle of the night. But America didn’t use to think of itself as the sort of nation that did things that way. Now it is proud of such actions? In his speech on Sunday night, Obama compared the killing of Bin Laden to other triumphs by America:

Tonight, we are once again reminded that America can do whatever we set our mind to. That is the story of our history, whether it’s the pursuit of prosperity for our people, or the struggle for equality for all our citizens; our commitment to stand up for our values abroad, and our sacrifices to make the world a safer place.

Let us remember that we can do these things not just because of wealth or power, but because of who we are.

These words are false. A killing is not comparable to the Apollo space program or the War on Poverty. It is not a moral achievement, let alone a technological one. If the Navy Seals had brought Bin Laden to the United States and we had then put him on trial, that would have been a moral achievement. But a nation need not be a democracy in order to kill its enemies. Revenge is not special. We can take it no matter who we are, and no matter who we become.