Another issue of the newsletter . . .

“All do not all things well,” sang Thomas Campion, and one thing that I don’t do well is the last few weeks before publication. My husband and I were trading anecdotes a few nights ago of how, in the month or so before my first novel was published, six years ago, I was a little sputtering butter warmer of rage and self-regard. I don’t want anyone to look at me! Why aren’t more people looking at me? was then the refrain of my days.

Frank Norris once said that he didn’t like to write but did like having written. It’s the sort of thing people like to hear from a writer, because it suggests that the writer is aware that there is something antisocial about the retreat from the world that is inextricable from writing, and that he is happy to reunite with the world at the end. It suggests, in other words, that the writer likes you.

What a lie. A writer is someone who likes other people much less than he likes to be able to say whatever he wants, in as rococo a way as he wants, at whatever length he wants, making jokes that only he may think are funny. For five years, while writing a novel, I have a life I never thought I’d be lucky enough to live: I sit alone for hours at a time, imagining people and a world, and growing fonder of them than of what is called the real world. And then, just when I think, Wow, I’ve finished a novel, what a good boy am I, I am told: You’re fired, sucker. Worse luck, my new job is salesman. Are my social media accounts tonally appropriate? What kind of pencil do I use? Are any of my characters based on people I knew in real life?

Overthrow is that cursed thing, a second novel. By “second novel,” I mean the book where one reaches—perhaps beyond one’s grasp. Herman Melville’s “second novel” was his third one, Mardi. (His actual second novel, Omoo, was just a sequel—more of the same of what was in his debut novel, Typee.) In Mardi, Melville attempted a novel that was also philosophy—allegorical, essayistic, stuffed full with oakum he had unpicked from his reading. It didn’t go over well. No, Herman, we liked it when you did boy’s-own adventure with ambiguous sexual frisson and anthropological tourism. Not watered-down Gulliver’s Travels but even more pedantic. For his next two books Melville went back to writing boy’s-own adventure with ambiguous sexual frisson and anthropological tourism, though he now appropriated the cultures of England and the American navy instead of those of islands in the South Pacific. In time the thwacked ambition of his “second novel” resurfaced, however. Moby-Dick is Mardi redux—a novel that is, once again, also a work of philosophy. But also with ambiguous sexual frisson and anthropological tourism, now of the culture of whaling. Melville couldn’t have written Moby-Dick if he hadn’t first written his failure Mardi. The challenge thus is not to mind failing. The proper stance to the reception of one’s work isn’t stovetop sputter but what I think of in my internal mental shortand as cool 1970s artist, wearing sunglasses and bellbottoms to her vernissage, cadging cigarettes from her friends in the back of the gallery, downing the yellowy white wine, not giving a shit because what’s important is to keep making the art, you know? Which of course is as much a lie as Frank Norris’s.

Quotes: “Les seuls vrais paradis, said Proust, sont les paradis qu’on a perdus: and conversely, the only genuine Infernos, perhaps, are those which are yet to come.” —Jocelyn Brooke, The Military Orchid

“A delightful feeling of rage seethed and bubbled over me as I read the letter. I was trembling a little and my palms felt sticky. Righteous indignation must be the cheapest emotion in the world.” —Denton Welch, Maiden Voyage

“If England is my parent and San Francisco is my lover, then New York is my own dear old whore, all flash and vitality and history.” —Thom Gunn, “My Life up to Now”

“The whole secret of a living style and the difference between it and a dead style, lies in not having too much style—being, in fact, a little careless, or rather seeming to be, here and there.” —Thomas Hardy, 1875 notebook, qtd. in Early Life

News: There’s an excerpt from Overthrow, the novel whose impending publication is causing me so much agita, in the August issue of Harper’s. In late June (gosh it’s been a while since I sent out a newsletter), the New Yorker website published my review of James Polchin’s Indecent Advances, a history of murders of gays in the 20th century and the so-called gay panic defense.

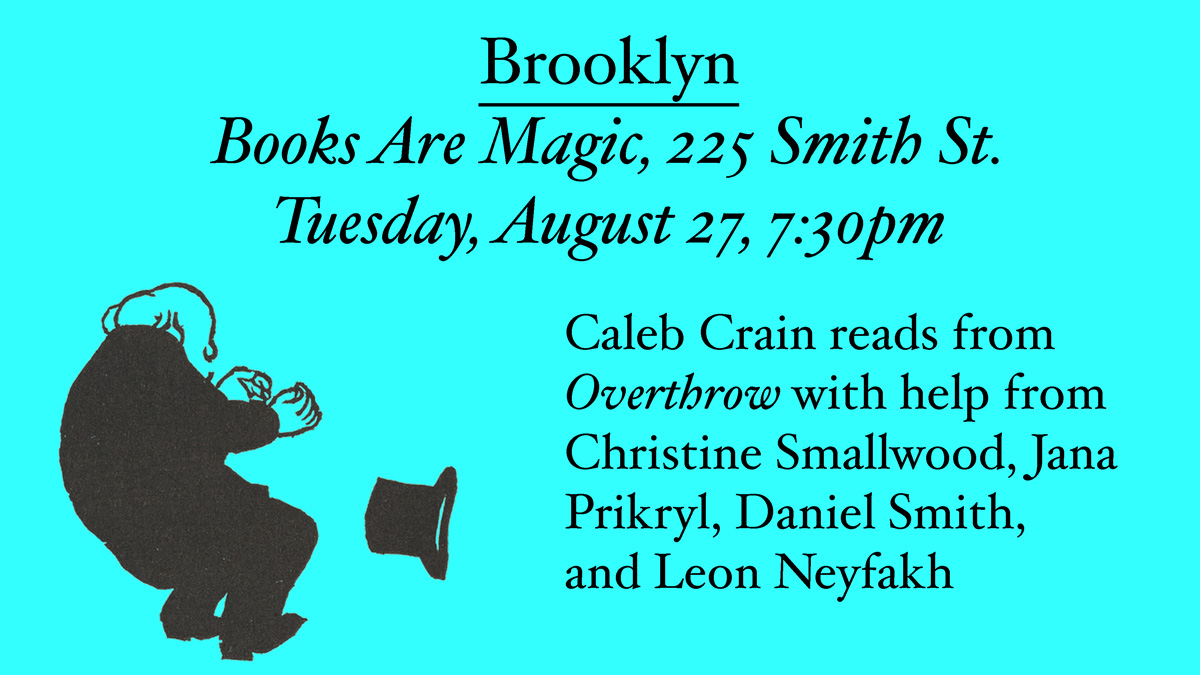

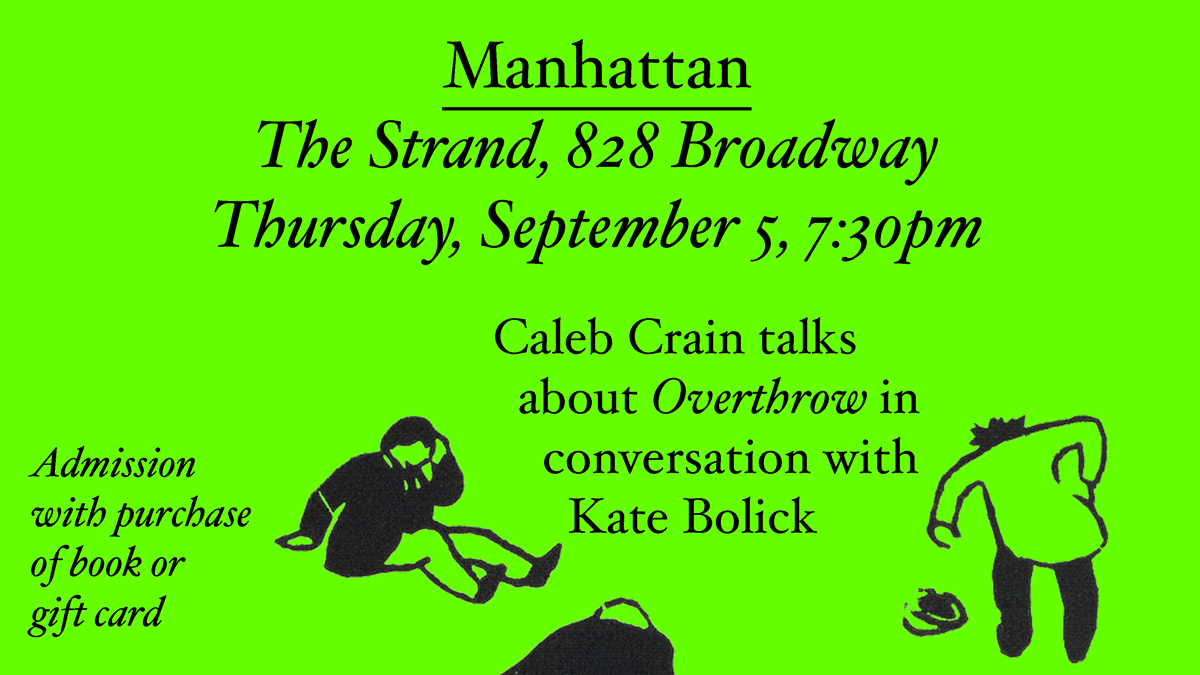

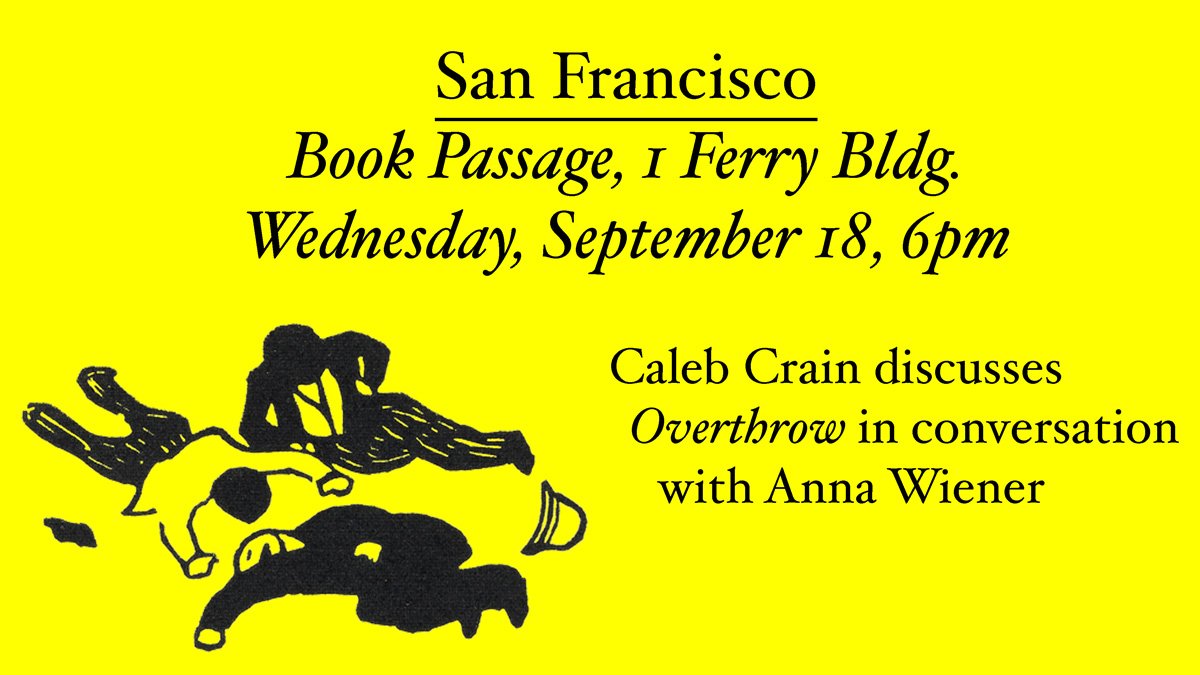

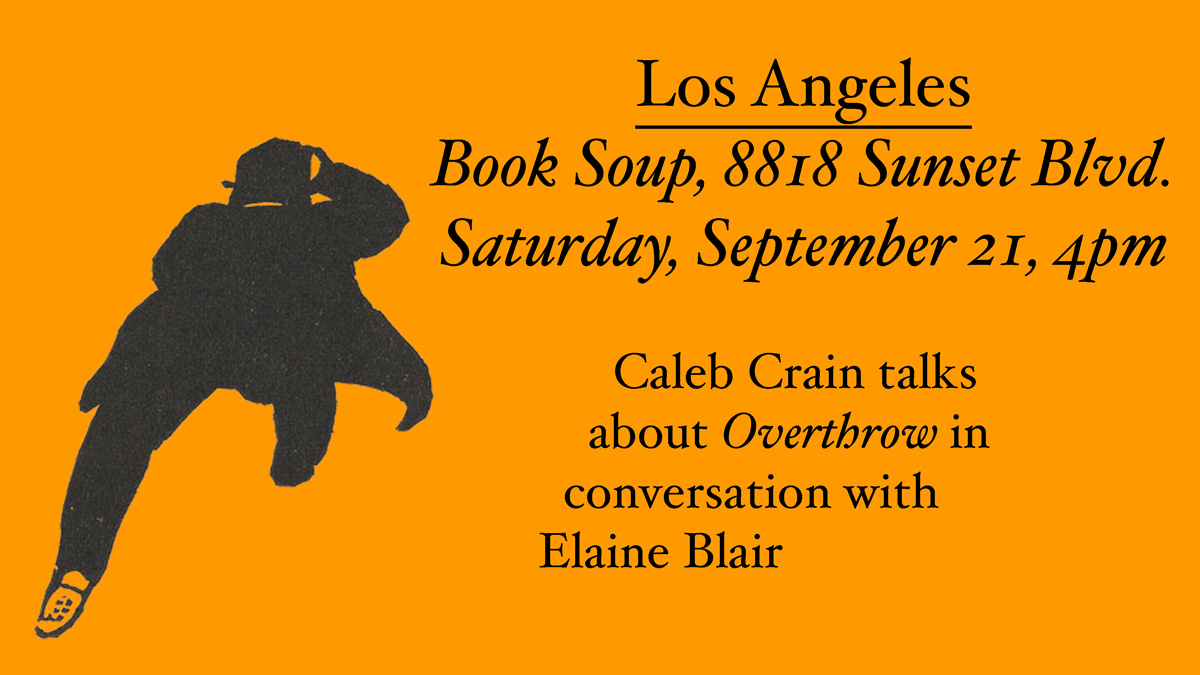

Below, in Technicolor, is the info on my bookstore events. Please don your bellbottoms and lengthen your sideburns and feather your hair and come:

Newsletter #3: Time lags, deadline philosophy, childish scribbles.

Once, when I was little, my family went on a drive-through safari, the kind where humans stay safely in a car while lions and giraffes roam freely. I remember that I objected angrily when my father paused the audio tour, which was on a cassette player. We were going to miss what the park ranger was saying! In those days, radios and televisions couldn’t be paused, and I didn’t see how a cassette player could work any differently. To hear the whole tour, surely we had to keep the device always on, no matter how far ahead of us the taped narrator got.

It isn’t obvious that writing takes place in time, maybe because reading doesn’t take place simultaneously or even necessarily at the same tempo. My childhood confusion is the writer’s secret weapon. But while there may be enough time, thanks to this décalage, to hide some of a writer’s flaws, there’s never enough to hide all of them.

Every book is the wreck of a perfect idea. The years pass and one has only one life. If one has a thing at all one must do it and keep on and on and on trying to do it better. And an aspect of this is that any artist has to decide how fast to work.

That’s from Iris Murdoch’s highly entertaining novel The Black Prince; a genre writer is justifying his mediocrity, and Murdoch is making a joke about her own prolificacy. But it happens to be true! Every piece of writing has a deadline—a moment past which it will no longer be possible to slot it into the context for which it was conceived. “Don’t take too long,” the editor of my first book, which was scholarly, said to me when I was dilly-dallying on a revision. “I don’t want those endnotes to get stale.”

Maybe women writers, historically more subject to interruption, have more often been thoughtful about the way writing is vulnerable to time. Here’s the novelist-heroine of Elizabeth Taylor’s novel A View of the Harbour:

“But it was through no fault of my own,” she thought, her mind reverting to those cracked and riven chapters of hers; all of her books the same, none sound as a bell, but giving off little jarring reverberations now here, now there, so that she herself could say, as she turned the pages (knowing as surely as if the type had slipped and spilt): “Here I nursed Prudence with bronchitis; here Stevie was ill for a month; here I put down my pen to bottle fruit (which fermented); there Mrs Flitcroft forsook me.”

The time of reading leaves marks, too. A couple of weeks ago, at the New York Antiquarian Book Fair, a bookseller let me page through a first edition of Edmund Spenser’s Colin Clout’s Come Home Again(1595). About halfway through the book, on a mostly blank verso, a child had scrawled in pencil, in large, loopy characters,

John

Cotton

1653

11 66 55 33

Tho-

mas

Cotton

The bookseller seemed a little startled. I said I thought the scribbles were charming, but I don’t think I looked enough like the sort of person who would actually be able to afford to purchase the volume to reassure him. “I don’t know,” he said. “It comes off a little strong, don’t you think?” When I got home, I asked Google but was unable to find a John or Thomas Cotton who was seven or eight years old in 1653. It also wasn’t until I got home that I wrote down the child’s inscription, from memory, which tends to be fallible. I see that the bookseller’s catalog entry does now mention it—I don’t know if it was added after the fair, or if it was there all along and I just now noticed it—and it records the inscription a little differently: “Thomas Cotton / 1653 / 165 / John / Cotton.”

The problem is more general, of course. Marcus Aurelius:

Frightened of change? But what can exist without it? What’s closer to nature’s heart? Can you take a hot bath and leave the firewood as it was? Eat food without transforming it? Can any vital process take place without something being changed?

Can’t you see? It’s just the same with you—and just as vital to nature.

A person is more or less a firecracker, in other words, and one’s sparkle, as a writer or in any other capacity, comes from the process of one’s self being used up.