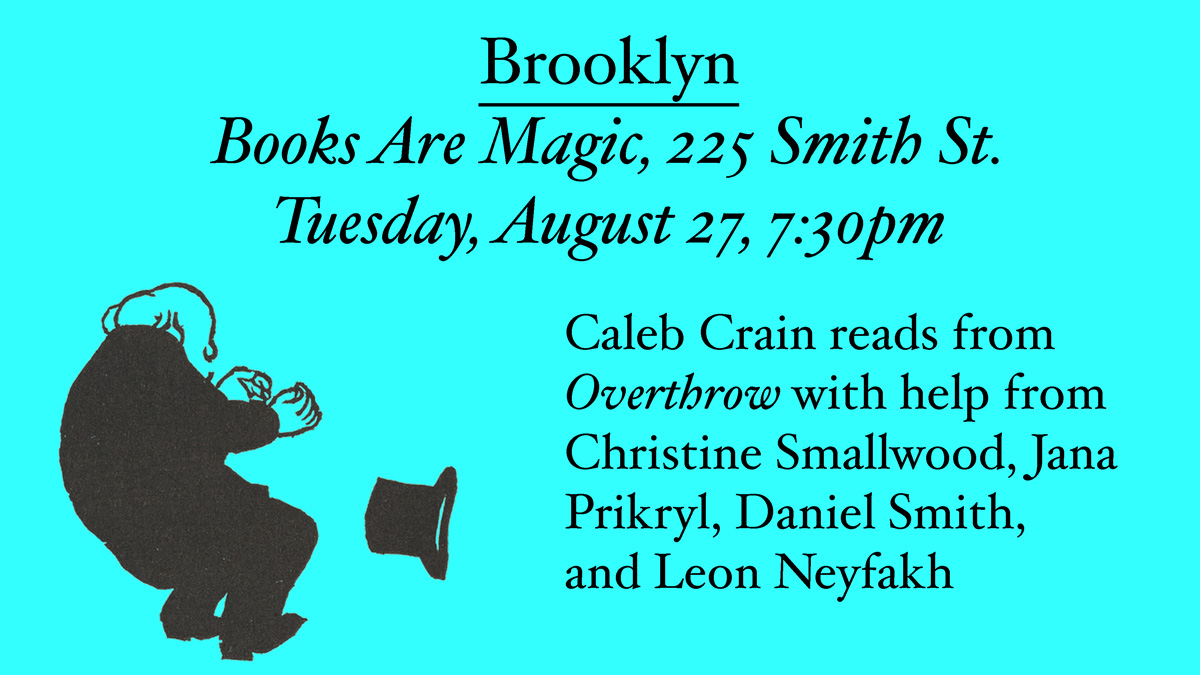

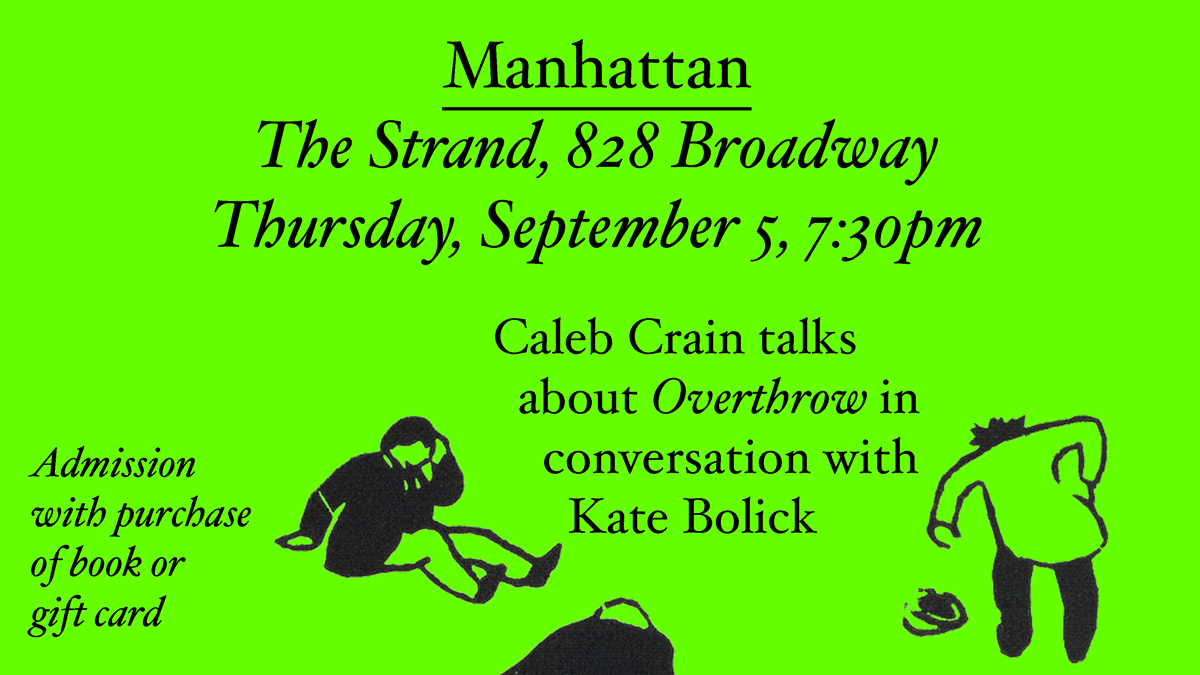

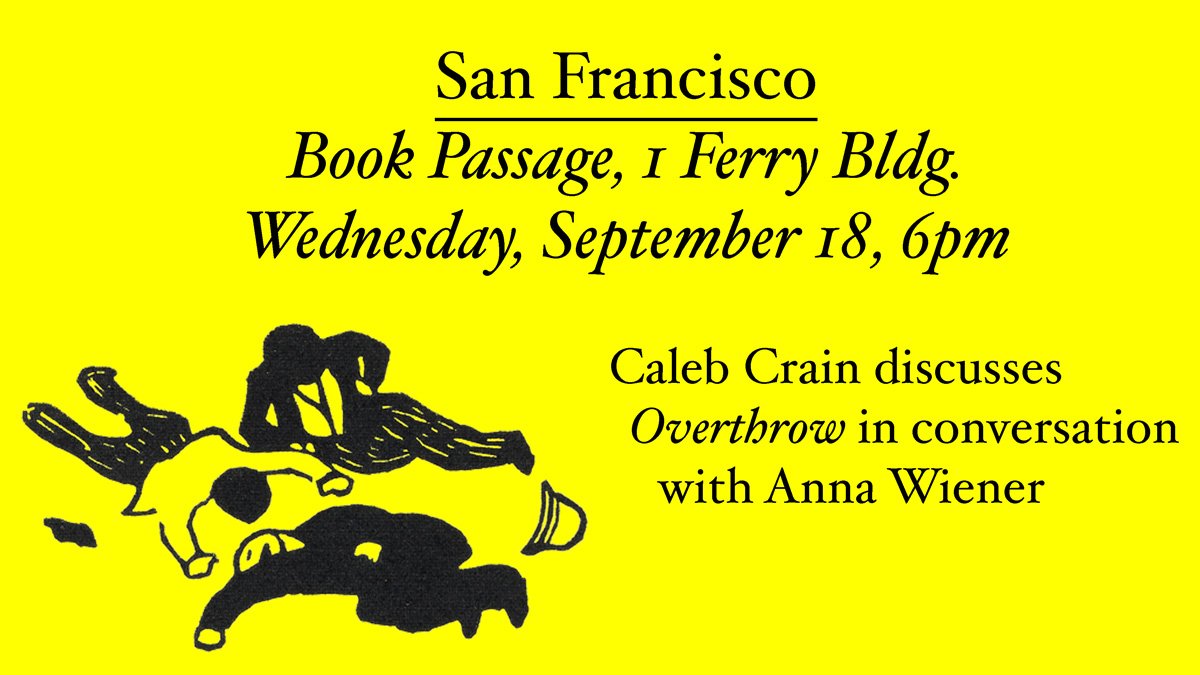

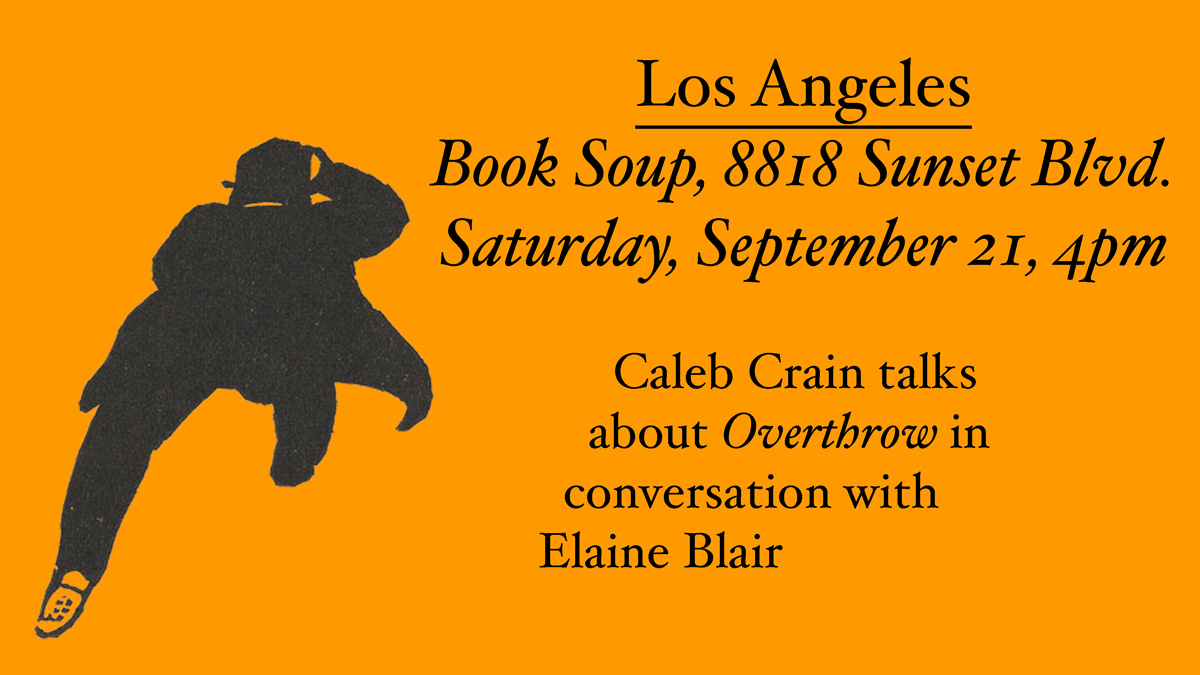

If you buy Overthrow at one of the bookstore events, which start next week, I can hand-stamp your copy.

Prospect Park, 8/21/2019

Locked out of Instagram, for the crime of telling my web browser to pretend to be a smartphone! So I’ll post here, where the photos don’t have to be square. Let me know if you can identify the tree in the last photo.

UPDATE, Aug. 22: Matthew Wills identifies the tree as an Eastern hophornbeam.

Working-class heroes

In the 26 August 2019 issue of The New Yorker, in an article titled “State of the Unions,” I review two new books on labor, Steven Greenhouse’s Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present, and Future of American Labor and Emily Guendelsberger’s On the Clock: How Low-Wage Work Drives America Insane. Please check it out!

A few source notes: Very helpful to me in writing the review were Jake Rosenfeld’s wonky deep dive into union data, What Unions No Longer Do (2014), Nelson Lichtenstein’s humane and insightful State of the Union: A Century of American Labor (revised ed., 2013), and Greenhouse’s earlier collection of war stories, The Big Squeeze: Tough Times for the American Worker (2008). I also drew on Philip Dray’s There Is Power in a Union: The Epic Story of Labor in America (2010), Joseph A. McCartin’s Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, the Air Traffic Controllers, and the Strike that Changed America (2011), and Kirstin Downey’s The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life and Legacy of Frances Perkins—Social Security, Unemployment Insurance, and the Minimum Wage (2009).

Most of the statistics in my review came from the books named above, with a few exceptions: In estimating that the proportion of union members in the labor force dropped from 12.2 percent in 1920 to 7.5 percent in 1930, I drew on Joshua L. Rosenbloom’s data, “Union membership: 1880–1999,” presented as table Ba4783 in Historical Statistics of the United States, Millennial Edition On Line, edited by Susan B. Carter, Scott Sigmund Gartner, Michael R. Haines, Alan L. Olmstead, Richard Sutch, and Gavin Wright (Cambridge, 2006) and on David R. Weir and Susan B. Carter’s data, “Labor force, employment, and unemployment: 1890–1990,” presented as table Ba470 in the same online sourcebook. In estimating that the proportion dropped from 35 percent in 1954 to 10.5 percent in 2018, I drew on Gerald Mayer’s Union Membership Trends in the United States (Congressional Research Service, 2004), p. 22, table a1, and on Barry Hirsch and David Macpherson’s Union Membership and Coverage Database from the Current Population Survey. In calculating the rate of strikes per decade, I drew on the data in the Bureau of Labor Statistics chart “Annual work stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers, 1947-2018.”

The researchers, mentioned at the end of my article, who found a link between children’s having union parents and earning more later in life were Richard Freeman, Eunice Han, David Madland, and Brendan V. Duke in their working paper, “How Does Declining Unionism Affect the American Middle Class and Intergenerational Mobility?” (2015, NBER 21638). The researchers who found that right-to-work laws suppress voter turnout and Democratic vote share were James Feigenbaum, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, and Vanessa Williamson in their working paper “From the Bargaining Table to the Ballot Box: Political Effects of Right to Work Laws” (2018, NBER 24259).

NYTBR on “Overthrow”

Julian Lucas has written a very thoughtful and generous review of my new novel Overthrow, published this morning in the online version of the New York Times Book Review:

What follows is, essentially, a 19th-century social novel for the 21st-century surveillance state. Frequently alluding to Henry James’s “The Princess Casamassima,” another story of young radicals, Crain subjects his characters to quandaries that test their precariously entwined identities. The novel almost dares readers to object to its inwardness — “It’s like there’s a new sumptuary law against introspection,” one of the four complains — but its tender, psychologically precise prose feels like a bulwark against the exposure it takes for a subject.

Leaflet #8

Another issue of the newsletter . . .

Hot and cold

“All do not all things well,” sang Thomas Campion, and one thing that I don’t do well is the last few weeks before publication. My husband and I were trading anecdotes a few nights ago of how, in the month or so before my first novel was published, six years ago, I was a little sputtering butter warmer of rage and self-regard. I don’t want anyone to look at me! Why aren’t more people looking at me? was then the refrain of my days.

Frank Norris once said that he didn’t like to write but did like having written. It’s the sort of thing people like to hear from a writer, because it suggests that the writer is aware that there is something antisocial about the retreat from the world that is inextricable from writing, and that he is happy to reunite with the world at the end. It suggests, in other words, that the writer likes you.

What a lie. A writer is someone who likes other people much less than he likes to be able to say whatever he wants, in as rococo a way as he wants, at whatever length he wants, making jokes that only he may think are funny. For five years, while writing a novel, I have a life I never thought I’d be lucky enough to live: I sit alone for hours at a time, imagining people and a world, and growing fonder of them than of what is called the real world. And then, just when I think, Wow, I’ve finished a novel, what a good boy am I, I am told: You’re fired, sucker. Worse luck, my new job is salesman. Are my social media accounts tonally appropriate? What kind of pencil do I use? Are any of my characters based on people I knew in real life?

Overthrow is that cursed thing, a second novel. By “second novel,” I mean the book where one reaches—perhaps beyond one’s grasp. Herman Melville’s “second novel” was his third one, Mardi. (His actual second novel, Omoo, was just a sequel—more of the same of what was in his debut novel, Typee.) In Mardi, Melville attempted a novel that was also philosophy—allegorical, essayistic, stuffed full with oakum he had unpicked from his reading. It didn’t go over well. No, Herman, we liked it when you did boy’s-own adventure with ambiguous sexual frisson and anthropological tourism. Not watered-down Gulliver’s Travels but even more pedantic. For his next two books Melville went back to writing boy’s-own adventure with ambiguous sexual frisson and anthropological tourism, though he now appropriated the cultures of England and the American navy instead of those of islands in the South Pacific. In time the thwacked ambition of his “second novel” resurfaced, however. Moby-Dick is Mardi redux—a novel that is, once again, also a work of philosophy. But also with ambiguous sexual frisson and anthropological tourism, now of the culture of whaling. Melville couldn’t have written Moby-Dick if he hadn’t first written his failure Mardi. The challenge thus is not to mind failing. The proper stance to the reception of one’s work isn’t stovetop sputter but what I think of in my internal mental shortand as cool 1970s artist, wearing sunglasses and bellbottoms to her vernissage, cadging cigarettes from her friends in the back of the gallery, downing the yellowy white wine, not giving a shit because what’s important is to keep making the art, you know? Which of course is as much a lie as Frank Norris’s.

Quotes: “Les seuls vrais paradis, said Proust, sont les paradis qu’on a perdus: and conversely, the only genuine Infernos, perhaps, are those which are yet to come.” —Jocelyn Brooke, The Military Orchid

“A delightful feeling of rage seethed and bubbled over me as I read the letter. I was trembling a little and my palms felt sticky. Righteous indignation must be the cheapest emotion in the world.” —Denton Welch, Maiden Voyage

“If England is my parent and San Francisco is my lover, then New York is my own dear old whore, all flash and vitality and history.” —Thom Gunn, “My Life up to Now”

“The whole secret of a living style and the difference between it and a dead style, lies in not having too much style—being, in fact, a little careless, or rather seeming to be, here and there.” —Thomas Hardy, 1875 notebook, qtd. in Early Life

News: There’s an excerpt from Overthrow, the novel whose impending publication is causing me so much agita, in the August issue of Harper’s. In late June (gosh it’s been a while since I sent out a newsletter), the New Yorker website published my review of James Polchin’s Indecent Advances, a history of murders of gays in the 20th century and the so-called gay panic defense.

Below, in Technicolor, is the info on my bookstore events. Please don your bellbottoms and lengthen your sideburns and feather your hair and come: