Today is the tenth anniversary of the day we brought Toby home from North Shore.

Americans may not have been better off in the 1950s, but they made more progress

In this morning’s New York Times, David Brooks, citing a new book by Steven Pinker, claims that there’s been more economic good news in America lately than has been appreciated.

Brooks (or Pinker) sets up a bit of a strawman by claiming that a “smothering orthodoxy” of economic observers have been wrongly idealizing the 1950s. In fact it isn’t the 1950s per se that gets idealized, in the tracts I’ve read; it’s the progress that the American economy made following World War II, which abruptly stopped in about 1973. And if you kick the tires on some of the numbers in Brooks’s article, this “pessimistic” assessment holds its own.

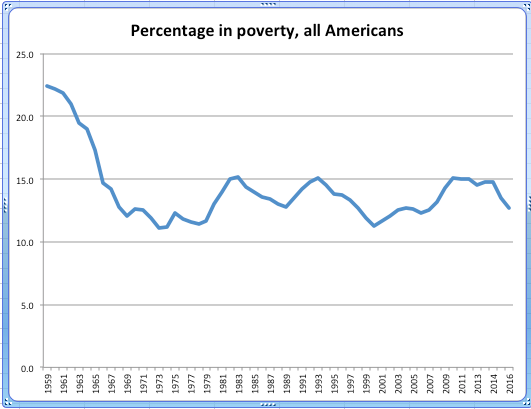

Brooks writes, for example, that “Between 1979 and 2014, . . . the percentage of poor Americans dropped to 20 percent from 24 percent.” I don’t have Pinker’s book, so I’m not sure what the underlying source for this claim is, but it is contradicted by the US Census, which reports that in 1979, the percentage of Americans living in poverty was 11.7 and by 2016 had risen to 12.7. By the word “poor,” therefore, Brooks and Pinker must mean something other than “living in poverty.” For a fuller picture, here’s a quick graph I made, using the Census’s data, of the proportion of Americans living in poverty between 1959 and 2016:

It seems to me that the natural inference to be made from this graph is that the Great Society programs of the 1950s and 1960s did an amazing job of combating poverty, but that progress has stagnated since the early 1970s—which happens to be the “gloomy” (as Brooks terms it) consensus among most economists studying such problems, however hopelessly conformist and noncounterintuitive that consensus may be.

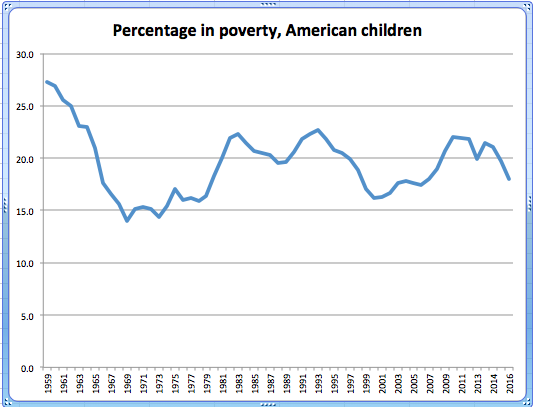

Again relying on Pinker, Brooks writes that “we should not be nostalgic for the economy of the 1950s” because at that time “A third of American children lived in poverty.” The US Census numbers do confirm that in 1959, 27.3 percent of Americans under the age of eighteen were living in poverty. However, by 1969, that proportion had fallen to 14.0 percent, rising again to 22.3 percent in 1983 (hi, Reagan!), after which it dithered for decades. It was at 18.0 percent in 2016. Which sounds to me, again, as if the Great Society accomplished wonders, and as if no serious progress, and in fact some retrenchment, occurred after that. Here’s a graph of American children living in poverty, 1959 to 2016:

Source: Table 3, Poverty Status of People, by Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin, U.S. Census Bureau

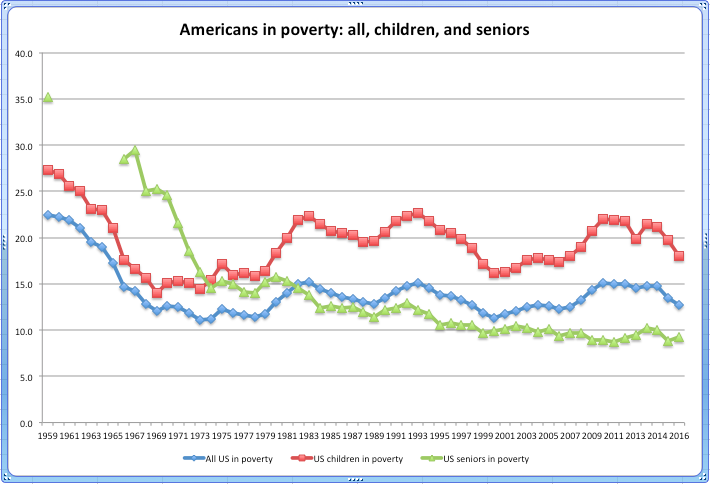

Brooks writes that “Sixty percent of seniors had incomes below $1,000 a year” in the 1950s. Again, I’m not sure what the underlying source for his claim is, but a flat number like that isn’t all that telling. Once more then, this time with feeling, here’s a graph of the percentage of American seniors living in poverty over the years. (I’ve combined it with the same percentages charted just above for all Americans and for American children):

Source: Table 3, Poverty Status of People, by Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin, U.S. Census Bureau. (Note: There are no data for seniors between 1960 and 1965.)

America has done better by its seniors than it has by its children or by its citizens generally (hi, Social Security!), but still, what the shape of the green line here tells me is that the yeoman’s work of ending poverty among seniors was done before 1973, and that further progress has only been incremental (and in the past twenty years, negligible).

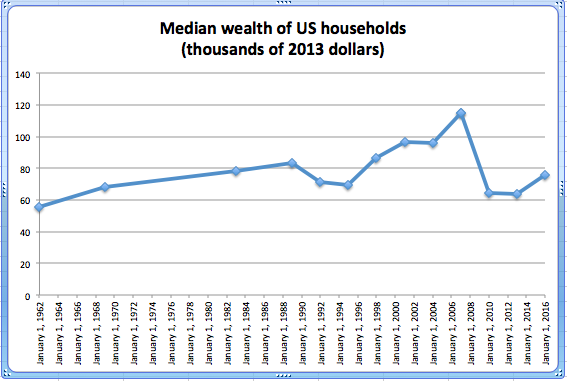

Bonus round: Brooks, channelling Pinker, also claims we shouldn’t look back fondly to the 1950s because back then “only half the population had any savings in the bank at all.” Again, I don’t know the source of this claim, but unless we know how much was in those savings account, the statistic probably doesn’t reveal much except changes in banking habits. More suggestive, I think, are the data that Edward N. Wolff has assembled about the median wealth of US households. Here is a hasty chart I made from some of Wolff’s data:

Sources: Edward N. Wolff, “Household Wealth Trends in the United States, 1962-2013: What Happened over the Great Recession?” NBER Working Paper No. 20733, December 2014, and “Has Middle Class Wealth Recovered?” presentation at the ASSA Meetings, January 6, 2018. (Note: In his 2018 presentation, Wolff gave his numbers in 2016 dollars, so I divided his 2016 number by 1.03 to put it into 2013 dollars in the graph here.)

Was the typical American household in the middle of the economy wealthier in the 1950s? Full disclosure, the 1950s aren’t on this chart, so there’s no saying. But pace Brooks and Pinker, the “gloomy refrain” about the American economy—the reason observers feel pessimistic—isn’t that the economy has gotten worse since the 1950s, but that in about 1973 it stopped improving the lives of average Americans. And that seems to me to be confirmed by the blue line here: the middle-of-the-road American household made steady progress in wealth during the golden age, but the last few decades took it on a bubble-and-burst ride that left it no richer than it was in the late 1970s.

Notes, 2017

The experience most easily shared on the internet is the experience of the internet. We thought, when the internet started, that it would be a revolutionary way for people to share with each other, and it is. But it’s biased against the sharing of anything that isn’t part of it. You don’t ever actually share your Thanksgiving dinner, say, over the internet. You share a picture of your Thanksgiving dinner, which, when you share it, you effectively surrender all ownership and control over. You give the picture to the internet, and other people then share in the picture that once was but is no longer yours. And so the internet, and our experience of it, gets larger and larger, while our experience of reality contracts, recedes, shrinks.

“But who is there that abstains from reading that which is printed in abuse of himself?” —Trollope, Phineas Finn

“The liar lives in fear.” —Adrienne Rich

As I grow older, my consciousness is beaten thinner and thinner, and by now it’s almost translucent, nacreous, like a film of mica or the surface of an abalone shell, opalescent, synesthetic, transposing feelings into textures and colors, not distinguishing itself from the weather.

“But then it is so pleasant to feel oneself to be naughty! There is a Bohemian flavour of picnic about it which, though it does not come up to the rich gusto of real wickedness, makes one fancy that one is on the border of that delightful region in which there is none of the constraint of custom,—where men and women say what they like, and do what they like.” —Trollope, Phineas Finn

It’s odd that as a matter of law, excretion is these days more heavily gendered than intercourse.

The last manifesto: What difference would it make to know that one was making art at the end of human time?

“She said Papa had to have me arrested, but Papa said he didn’t have to do but two things—die and stay black.” —Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road

“A cell that has reached metabolic equilibrium is dead! The fact that metabolism as a whole is never at equilibrium is one of the defining features of life.” —Jane Reece, Campbell Biology, qtd. in David A. Moss, Democracy: A Case Study

“As the colony shrinks, the gossip and private jokes grow, I suspect, increasingly animated, like the thrashing of fish in a pond that is drying up.” —James Merrill on the subject of life in Alexandria, Egypt, qtd. in Langdon Hammer’s biography of him

convive (n.): member of a group who dine together; participant in a feast

“He is a rather gifted poet, I’m afraid, but terribly uneducated, and a real vampire; one is Drained after an hour with him, while he of course bursts with energy from his bloodless convives.”

—Merrill, qtd. in Hammer, James Merrill: Life and Art

“That poem, I mean, is not written to you, David, in the sense that this letter is. Though it addresses you, don’t forget that pronouns like You or I or We are also deep in the nature of language and help bring it to life. It is for you—it couldn’t have been written without what you showed me by way of landscape and happiness and, yes, tension. Don’t take it too personally: as a gift, if you will; as a message, no.” —Merrill, qtd. in Hammer’s bio

The dream is that the universe exists the way that it does because there’s no other way for it to.

When you drive past a wreck, your yen to look at the gore and mess is eventually overruled by the need to focus on the road ahead. I’m waiting for that moment.

destrier (n.): a medieval knight’s warhorse, a charger

“A group of English knights . . . rode forward on their great destriers to cut off the retreat.”

—Christopher Given-Wilson, Edward II

remora (n.): obstacle, hindrance; originally, an eel thought to attach itself to a ship to slow it down

“The Scots were goading parliamentary leaders who feared Strafford more than they feared the king: ‘the great remora to all matters is the head of Strafford.’ ”

—Mark Kishlansky, Charles I

They tell you that Robin Hood stole from the rich and gave to the poor, but they don’t tell you that the rich in question were monks and that the poor were gentry who couldn’t pay their debts.

My youth the glass where he his youth beheld,

Roses his lips, my breath sweet nectar showers,

For in my face was nature’s fairest field,

Richly adorned with beauty’s rarest flowers.

My breast his pillow, where he laid his head,

Mine eyes his books, my bosom was his bed.

—Michael Drayton, Peirs Gaveston

Is lying illocutionary or perlocutionary?

All the people who don’t know how to bicycle are bicycling again, and the air is florid with my curses.

damascene (v.t.): to ornament a metal object with inlaid designs of gold or silver

“A beautiful double-barreled hammer gun damascened with silver, its blue-black barrels worn paper-thin with firing”

—Richard Hughes, The Fox in the Attic

upas (n.): a poisonous Javanese mulberry tree, supposed capable of destroying all animal life nearby; often used metaphorically

“. . . he aims to be a kind of social upas, to kill conversation anywhere within reach of his shadow”

—Hughes, Fox in the Attic

Wordsworth turned from nature as a raw material for exploitation to nature as a resource for moral renewal and aesthetic refreshment. The poetic move had something to do with the shift from agriculture to industry: a new class of people were arising who no longer needed to look at a landscape for what it offered to them for survival. Will human labor undergo a similar revaluation? It probably won’t feel as liberating, because it’s not that a new class of people won’t need to look to their labor for survival, but that they simply won’t be able to any more. Their need may well persist, but their labor will no longer be able to supply it. The freedom may lead therefore not to a sublime access of meaningfulness but to a painful death of meaning. You will be free to learn to paint watercolors or play the ukelele, but your effort of self-improvement will only make you feel all the more worthless.

“Mr. Bartlett told me one story of Thoreau which I have not seen in print. . . . A number of loafers jeered at him as he passed one day, and said: ‘Halloo, Thoreau, and don’t you really ever shoot a bird when you want to study it?’

“ ‘Do you think,’ replied Thoreau, ‘that I should shoot you if I wanted to study you?’ ” —Hector Waylen, “A Visit to Walden Pond,” qtd. in Walter Harding, Thoreau, Man of Concord

A reality TV show that is staged is referred to euphemistically as “produced.” When a reality show is done in a more straightforwardly documentary style, it’s called a “follow show.”

“One of those heavenly days that cannot die” —Wordsworth, “Nutting”

Christopher Caldwell claims that addicts do choose addiction, and this seems plausible to me. It’s terrifying to know that one’s actions aren’t by any logic necessary, and addiction supplies all the necessity that anyone could ever need. Like tightening all the give out of a hinge.

And you must love him, ere to you

He will seem worthy of your love.

—Wordsworth, “A Poet’s Epitaph”

“And if I am asked today to advise a young writer who has not yet made up his mind what way to go, I would try to persuade him to devote himself first to the work of someone greater, interpreting or translating him. If you are a beginner there is more security in such self-sacrifice than in your own creativity, and nothing that you ever do with all your heart is done in vain.” —Stefan Zweig, World of Yesterday

What most of you don’t realize is that it isn’t safe to agree with me.

drey (n.): squirrel’s nest

“Squirrel’s drays, or ‘huts,’ as they are locally known, contain new-born young.”

—Edward Thomas, “A Diary in English Fields and Woods”

“He that would be well old, must be old betimes.” —George Herbert, Outlandish Proverbs

weal (n.): a ridge raised on the flesh by a blow

“I stepped on to the wing and got awkwardly into the cockpit beside him, giving my forehead a good unpremeditated whack on the edge of the top plane. I shut the door and bolted it awkwardly. Then I ran my finger along the weal in the roots of my hair.”

—David Garnett, A Rabbit in the Air

tedder (n.): an instrument for spreading out new-mown grass, so that it will dry

“Below me the fields of stubble had been brushed and combed with horse-rakes and tedders until they were better groomed than French schoolboys leaving the barber’s shop.”

—Garnett, Rabbit

croodle (v.i.): draw oneself together because of the cold, huddle for warmth

“And croodling shepherds bend along / Crouching to the whizzing storms.”

—John Clare, “February—A Thaw”

“The moving accident is not my trade.” —Wordsworth, “Hart-Leap Well”

“Be this your wall of brass, to have no guilty secrets, no wrong-doing that makes you turn pale.” —Horace, Epistolae, qtd. in Byron, Letters

lattermath (n.): the second mowing, the second crop of grass

“It was upon a July evening.

At a stile I stood, looking along a path

Over the country by a second spring

Drenched perfect green again. ‘The lattermath

Will be a fine one.’ So the stranger said,

A wandering man.”

—Edward Thomas, “Sonnet 5”

But in a co-work space would I be able to curl up on the floor and sob?

“Spring could do nothing to make me sad.” —Thomas, “May 23”

“I’ve always been sceptical of people who claim to understand [Wallace] Stevens.” —Bob Silvers, qtd. in Thomas Meaney, “The Legendary Editor”

“As a man is prepared in his mother’s womb to be brought forth into the world, so is he also after a sort prepared in this body and in this world to live in another world.” —Duplessis-Mornay, A Work Concerning the Trueness of the Christian Religion (1587), qtd. in the notes of my edition of Sidney’s Old Arcadia

Pyrocles vanishes completely into the persona of Cleophila; Sidney does almost nothing to remind the reader that she is “really” Pyrocles. Trollope, similarly, does not say that the marchioness of Hartletop, say, was formerly Griselda Grantly. It’s the reader’s task to remember the human being behind the new title—the hermit crab in the new shell. The contrast between the obscured humanity and the false disinctiveness is part of the humor but also the pathos: society doesn’t know who we are, or really care to know.

plummet (n.): a stick of lead, for writing or ruling lines

“On the flyleaf at the very end is a faint price written in plummet probably of the 14th of 15th century, ‘xxii lb. xix s.,’ 22 livres and 19 sous.”

—Christopher de Hamel, Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts

“To persons standing alone on a hill during a clear midnight such as this, the roll of the world eastward is almost a palpable movement. The sensation may be caused by the panoramic glide of the stars past earthly objects, which is perceptible in a few minutes of stillness, or by the better outlook upon space that a hill affords, or by the wind, or by the solitude; but whatever be its origin, the impression of riding along is vivid and abiding.” —Thomas Hardy, Far from the Madding Crowd

Here, in fact, is nothing at all

Except a silent place that once rang loud,

And trees and us—imperfect friends, we men

And trees since time began; and nevertheless

Between us still we breed a mystery.

—Edward Thomas, “The Chalk Pit”

On a Friend Who Is a Straight Novelist Tweeting out a Translation of Rimbaud’s Poem about How Our Butts Aren’t Like Theirs #titlesofunwrittenpoems

wimble (v.t.): make a rope by using a special instrument that twists together strands of straw

“ ‘What have you been doing?’

“ ‘Tending thrashing-machine, and wimbling haybands, and saying “Hoosh!” to the cocks and hens when they go upon your seeds . . .’ ”

—Hardy, Madding

Whatever wind blows, while they and I have leaves

We cannot other than an aspen be

That ceaselessly, unreasonably grieves,

Or so men think who like a different tree.

—Edward Thomas, “Aspens”

hikikomori (n.): complete withdrawal from society for a long period; a person undergoing such withdrawal

“Above all, they are isolated, scattered hikikomori sitting alone in front of a screen.”

—Byung-Chul Han, In the Swarm

“Solidarity is vanishing. Privatization now reaches into the depths of the soul itself.” —Han, Swarm

The internet coats with indifference any insight that might endanger that way it likes to do business.

“Define extreme candor.” —Matthew Keys, during his interrogation by FBI agent John Cauthen

When the cell phone became the phone, what had once been the phone had to be called the landline. What will we call cars that aren’t driverless? Steer-it-yourself cars? Driver-dependent cars?

“. . . his face showed that he was now living outside his defences for the first time, and with a fearful sense of exposure.” —Hardy, Madding

neap (n.): the tide following the first and third quarters of the moon, when the difference between high and low tides is least

“The spring tides were going by without floating him off, and the neap might soon come which could not.”

—Hardy, Madding

Every summer I learn the hard way anew that any sunblock that one buys at Whole Foods smells and feels like peanut butter.

archivolt (n.): the lower, or under, curve of an arch, stretching from impost to impost; intrados

“. . . it was the village schoolmaster who directed the festivities and arranged the bunting (some of it frankly red) to greet my father on his way home from the railway station, under archivolts of fir needles and crowns of bluebottles, my father’s favorite flower.”

—Vladimir Nabokor, Speak, Memory

“The new man will finger instead of handling.” —Han, Swarm

“It is difficult for a woman to define her feelings in language which is chiefly made by men to express theirs.” —Hardy, Madding

If I could write poems, I would write one that rhymed curtilage and sortilege.

frass (n.): the excrement of larvae

“In a sweating glass jar, several spiny caterpillars were feeding on nettle leaves (and ejecting interesting, barrel-shaped pellets of olive-green frass).”

—Nabokov, Speak, Memory

Overheard in the park . . .

Father: It goes priest, bishop, cardinal, pope.

Son: What about abbott?

Father: Umm.

There’s so much information about the wind when you walk under trees.

The crucial mistake the young writer makes is thinking that if he can write the kind of writing he admires he will be able to make a living.

adespota (n.): literary works not claimed by or attributed to an author

“In the process of verification they must have traced many of Peacock’s adespotic quotations.”

—R. W. Chapman, Review of English Studies, 1925

Having one’s secondary-process thinking only very lightly overlaid over one’s primary-process thinking may be aces for one as a writer but it is no good as a dental patient.

“I ate and drank slowly as one should (cook fast, eat slowly) and without distractions such as (thank heavens) conversation or reading. Indeed eating is so pleasant that one should even try to suppress thought.” —Iris Murdoch, The Sea, the Sea

“Oftener than you might think what human beings actually do is what they want to do.” —Murdoch, Sea

kipple (n.): objects that have lost their functionality through disuse or decay

“Kipple is useless objects, like junk mail or match folders after you use the last match or gum wrappers or yesterday’s homeopape.”

—Philip K. Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

goupen (n.): amount that can be held in two cupped hands

“We did not exactly lie in the thoroughfare of those mighty masses of foreign commodities, the throughgoing of which left, to use the words of the old proverb, ‘goud in goupins’ [gold in goupens].”

—John Galt, The Provost

“. . . laws are not made like lime twigs or nets to catch everything that toucheth them, but rather like sea marks to avoid the shipwrack of ignorant passengers.” —Sidney, Old Arcadia

“Germaine opened the fridge door and looking in said, ‘What do I have for my darlings? What do I have for my darlings to eat?’ She reached inside. The cats had their noses into the bottom of the fridge. ‘Oh darlings,’ she said, ‘you’re so lucky. Here’s testicle.’ And she took out, in her hand, a large, yellowish lump with fleshy tissue hanging from it and threw it, with a soft wed thud, on the big wooden chopping block on the table at which I was standing with the open bottle of wine.” —David Plante, Difficult Women

Is every song on Haim’s new album about drunk-dialing the one-night-stands of yesteryear?

It wasn’t the warmest tentacle. #firstlinesofunwrittennovels

Dreamed that I was sitting in a library reading a newspaper and a woman sat down beside me who didn’t know what it was and called it a “poster.”

In Hans Keilson’s The Death of the Adversary, the narrator’s defense of B.—that is, Hitler—is that B. doesn’t really mean what he says but is only anti-Semitic for rhetorical purposes. This is like the defense made today of Trump: it’s just the way he talks. Keilson’s narrator: “I don’t know whether he means it all as seriously as we think. He pursues certain aims and needs an enemy, as a kind of peg on which to hang his propaganda. At bottom he means himself.” This, too, is said today of Trump. Trump’s former ghostwriter repeats as a drumbeat that every insult Trump delivers is a self-description.

“What you’re after is something impossible: you are trying to plaster up the crack that runs through this world, so that it becomes invisible; then, perhaps, you’ll think that it doesn’t exist any more.” —Keilson, Death of the Adversary

mandrel (n.): a cylindrical rod around which metal or another material is forged or shaped

“If you make a condom that’s less than half the volume of a standard condom, you’re not going to fill it with as much water, or it’s not long enough to stretch on the mandrel for airburst testing.”

—Pam Belluck, “A Condom Maker’s Discovery,” New York Times, 17 October 2017

It is unsurprising that the foolish do not understand how the intelligent see things. But it turns out that the intelligent rarely understand how the foolish see things, either.

“I basked in the thought that I was doing justice to my enemy. At that time my own neck was not yet in danger.” —Keilson, Adversary

The social dead zone of entering one’s PIN in a card reader, instead of interacting with the cashier. The even greater dead zone of the self-checkout kiosk. On the subway, the few of us still reading paper-based material are more accessible to the panhandlers and performers than those in headphones watching shows on their phones. When a stranger smiles on the subway now, he is as likely to be responding to some media he is privately consuming as to— [My note breaks off here, presumably because my train arrived at its station]

The way David France tells the story, in How to Survive a Plague, Larry Kramer was one of the first intellectuals to appreciate at its true value the news of the “gay cancer” because he was angry about the hypersexualization of gay culture and was gratified by the bad news. And this gratification on his part was widely recognized and was used to discredit Kramer and minimize the gravity of the news. There might be a contagious gay cancer, the argument went, but it was the sort of thing Kramer wanted to hear, and he’d be trumpeting it whether or not it was true. Which may have been correct, but was no argument against the truth of the news. In fact, it’s probably always the case that the first to sound an alarm are those who have been waiting for the bad news and who take a perverse pleasure in it, human nature and attention being what they are. This doesn’t mean that all Chicken Littles are always right, but it does mean that their being Chicken Littles is no evidence that the sky is not falling. (Cf. the way no one took seriously Michael Moore’s prediction that Trump would win.)

France says that Randy Shilts was the first gay-media reporter ever to cross over into the mainstream. If I had been born ten years earlier, my career would have been impossible.

wicket (n.): an opening or window with a grille; a ticket office, esp. at a bank

It being Wednesday the wickets in the Post Office were closed, but I had my key.

—Alice Munro, “Postcard”

It’s okay to put death in every story. In the real world, death is in every story.

The impulse to show off creativity coincides with actual talent so rarely that when one encounters shown-off talent, one is tempted to indulge it, almost out of a sense of relief. But maybe in fact it shouldn’t be encouraged even then.

Peter, pretend-sternly: “That’s what comes of staying up late reading the introductions to all the books about the end of democracy.”

“And, indeed, he had so cleverly learned the ways of the wealthy, that he hardly knew any longer how to live at his ease among the poor.” —Trollope, The Eustace Diamonds

“When Bob Bibleman unlocked the door of his one-room apartment, his telephone was on. It was looking for him. ‘There you are,’ the telephone said.” —Philip K. Dick, “The Exit Door Leads In”

Sometimes the sign of a tree’s death is that its leaves do not fall.

“Then he realized that his own image stood before him, the image of himself as he had been thirty years before. ‘Have I been reincarnated in his form?’ Casanova asked himself. ‘But I must have died before that could happen.’ It flashed through his mind: ‘Have I not been dead a long time? What is there left of the Casanova who was young, handsome, and happy?’ ” —Arthur Schnitzler, “Casanova’s Homecoming”

Or must I be content with discontent

As larks and swallows are perhaps with wings?

—Edward Thomas, “The Glory”

“Envoy” in the Paris Review podcast

In episode 5 of the @ParisReview podcast, I read my short story “Envoy” (starts at timestamp 25:30).