[Four years ago, I figured out a way to make an interlinear gloss appear and disappear when you clicked on the lines of a poem. Then I switched my blog-hosting software, and all the magic crumbled. But I found a WordPress plug-in yesterday called Collapse-pro-matic, and after a few hours of kludgy hacking, Thomas Wyatt is back in action, as you’ll see if you click on any of the lines of verse below. —CC, 22 September 2016]

They Flee from Me

by Thomas Wyatt

Remembering lost lovers is a bittersweet pleasure.

They flee from me that sometime did me seek

Thomas Wyatt seems to be looking back at his lovers from middle age, though he can’t have been too old when he wrote it; he didn’t live to be forty. When this poem was first published, in an anthology that appeared in 1557, a decade and a half after his death, the editor gave the following explanation of what happens in it: “The lover showeth how he is forsaken of such as he sometime enjoyed.” By tradition, men hunt, and women are hunted, but love didn’t always quite work that way even in the sixteenth century, and no sooner does Wyatt introduce the metaphor of hunting than he messes with it. In the very first line, the poet is hunting creatures that once hunted him.

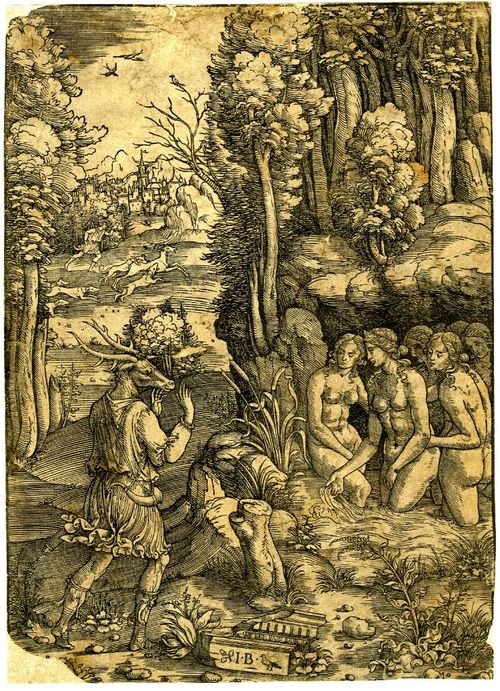

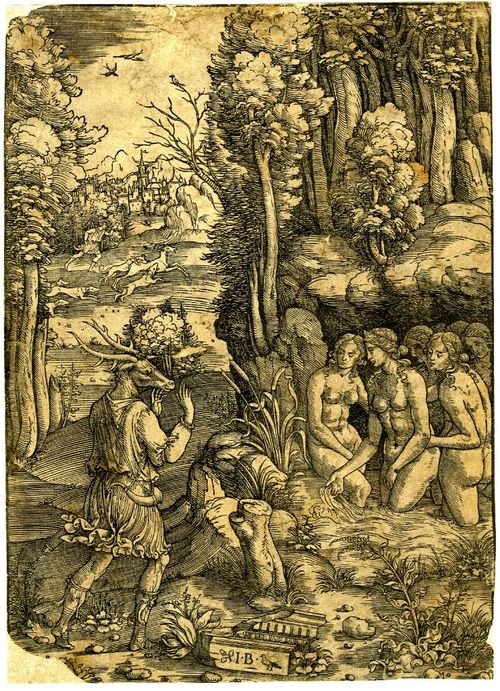

Are they deer? “To stalk,” wrote one of Wyatt’s 19th-century commentators, “means to steal softly with noiseless step.” But a hunter also stalks. Naked feet, stalking—I imagine that in the darkness, the poet’s bedroom chamber has become overgrown with verdure, and maybe even forested, like Max’s in Where the Wild Things Are. Or perhaps the creatures are ghosts. Infidelity and death are two ways of losing a lover to time.

As the poet remembers how the creatures came to him, his memories of them also seem to approach, advancing from the simple past to the present perfect tense. They’re so docile that the reader may wonder whether hunting really is the metaphor in play. The creatures seem to have offered themselves to the poet freely, like the animals who submitted themselves to Adam for naming in the Garden of Eden.

Tame in one line, wild in the next. However accustomed to his touch the creatures once were, they don’t know his hand any more; they no longer come when called. I’m reminded of Lewis Carroll’s Fawn, who lets Alice clasp his neck as the two of them walk together through the wood where things have no name, only to shy away from her once he discovers, upon emerging from the wood, that he’s prey and she’s a predator.

The note of danger returns the reader to his first guess: The poet does seem to be describing an episode of hunting, after all. Hunters lay lures; they hope their victims don’t perceive the threat until too late. But the word danger is rhymed with remember and chamber, raising the complicating possibility that, whatever direction the vector of hazard may have pointed in the past, it’s the poet who’s at risk now, in peril for having ventured so far into memory.

Maybe it’s hard to distinguish hunting from domestication because the fate of a cow or pig isn’t all that different from that of a hunted deer. Domestication is an act of hunting that takes place in slow motion—over the course of the animal’s lifetime—in a confined space.

Suddenly the creatures have escaped the confined space; abruptly the metaphor of hunter and deer has dropped away. By betraying an interest in change for its own sake, the fugitives reveal that they have the moral complexity and disreputableness of human beings. I suppose you could describe the “seeking” of the creatures as foraging, if you insisted on finding a way to continue the venatorial metaphor, but I suspect that the important discovery here is that metaphor isn’t able to hold them.

The poet’s tone of voice shifts. Perhaps because he made himself vulnerable in the first stanza, he starts the second one with a touch of bluster.

Thanked be fortune, it hath been otherwise

It would hardly be courtly, let alone gentlemanly, for a poet to boast of his conquests. But after a confession of general romantic failure, in what sounds like middle age, a little boasting about his youth seems licensed. “I graunte I do not professe chastite,” Wyatt once admitted.

Let me tell you about this one time when I totally scored.

The poet is undressing the woman, or rather, recalling how her clothes fell from her.

Notice that it’s she who caught him. Rather gallantly, he resists describing her naked body, even while describing how it was revealed, until he comes to her arms. It isn’t indiscreet to describe a woman’s arms, and somehow the inherent modesty of arms makes it all the more poignant that he lingers over them.

This is an immortal line. Wyatt’s 19th-century commentator is at pains to insist on “the propriety of this image,” maintaining that it represents a convention of chivalry: “whenever a lady accepted the service of a knight, . . . she gave him a kiss, and this was considered to be an inviolable bond of obligation.” No doubt the kiss that Wyatt received did play on a chivalric convention, but the bond in question turned out not to be inviolable, and it’s the erotic intensity of the image that brings tears to my eyes. I know that the phrasing of the woman’s question doesn’t sound colloquial today, but I feel confident that the rhythm of it was natural in Wyatt’s day. In fact I feel confident that a woman once existed who said these exact words to Wyatt while he was in love with her—I feel as if I’ve heard her say them to him—and I’m sorry, but I imagine that she was doing more than kissing him while she spoke. “Dere hert,” is how the words are spelled in the surviving manuscript and in the first publication of the poem. The poet has himself become the deer and the hart, not clearly distinguished from dear and heart in 16th-century orthography. He was and still is willing to be taken. It’s for this moment, and for the concentration of pleasure into this moment, that she once came into his room, that he is revisiting the memory now, and that we are reading the poem.

In the third stanza, the poet’s tone of voice shifts again, turning conversational, even plain. He acknowledges that he has asked us to believe in the reality of a moment that even he has trouble still believing in.

It was no dream: I lay broad waking.

Today we would say wide awake rather than broad waking, but the meaning is the same. He experienced the woman’s love with the channels of his senses completely open.

He has been too kind to her. By gentleness he means not just the mildness of his manners but also the gentility of them. His highmindedness. His willingness to play the role of Lancelot to Guinevere—to let her go back to King Arthur if she wants to (Wyatt was long thought to have been a lover of Anne Boleyn’s before she became the wife of Henry VIII, though the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography doubts the liaison), or to let her take up with another knight altogether. Or maybe there’s a note of self-reproach in the poet’s description of himself as gentle. Maybe he means that he didn’t hold on to her hard enough.

Already in the 16th century, seeing other people was a bold thing that lovers tried, in order to prove they weren’t hamstrung by conventional morals. Fitzgerald, on the Jazz Age: “I remember a perfectly mated, contented young mother asking my wife’s advice about ‘having an affair right away,’ though she had no one especially in mind.”

Leave means “permission,” and of her goodness, “thanks to her graciousness.” But puns multiply in the poem’s closing lines, and her goodness also means “her goodness,” which the poet would rather not leave. Note that this line, like the two preceding it, is in the present tense. It turns out that the affair must not have happened in the poet’s long-ago youth, as the first two stanzas suggested; the loss of it is happening now. The poet and the woman have just recently had the conversation where they decided on their new terms, and they’re still repeating the terms to themselves, in an effort to convince themselves of the rightness of them. From the first stanza to the third, there has also been a shift from plural to singular, from they to her. It’s a poem crafted by means of what people in Hollywood call “cheating”: the artful dovetailing of unmatched parts to create an impression of unity.

It’s strange that newfangled still sounds like a novelty word, when it happens to be quite an old one. One of Wyatt’s 20th-century commentators observes that “the word is often used by Chaucer.” In Wyatt’s day it could refer to both an item that is “objectionably modern,” as the OED puts it, and to an immoderate inclination to try such items. In the ballad “The Boy and the Mantle,” for example, Queen Guinevere is attracted to a cloak, despite being told that it has the power to expose unfaithful wives, because “the Ladye shee was new fangle.” Wyatt and his lover have given each other permission to try a new and trendy way of being in a romance, which may amount to a propensity for new and trendy lovers.

Kindly here means both “with kindness” and “in kind”: since Wyatt is being treated with such kindness, . . . since Wyatt is being given the kind of treatment he gave his lover, . . . Both meanings are ironic. The implication is that Wyatt has no right to complain of his lover’s so-called goodness and so-called gentleness, because he started it. She’s only repaying him in his own coin. According to one of Wyatt’s 20th-century commentators, the word served in this line may suggest a reversal: the courtly lover is being served by his mistress instead of serving her. But what kind of cavalier serves his mistress by loving others?

If Wyatt is getting what he deserved, namely, a taste of his own medicine, what does his lover deserve? On a first reading the question sounds almost rhetorical, as if the poet were making a half-hearted attempt to be cynical at the expense of his old lover, so as to prove to himself that he doesn’t miss her. But it might be a real question. Perhaps the answer is “Wyatt,” since his lover doesn’t seem to have behaved any better (or worse) than he did. Or maybe the most that she deserves is this poem—a memory of the happiness they briefly made with each other, set somewhat ironically in verse—their real love recalled and lost all over again in a courtly form.